MANILA, PHILIPPINES – Two years after the war in Marawi, its craft communities continue to rebuild their lives and homes through their exquisite heritage products. As seen at recent trade shows such as Manila FAME and the Philippine Arts and Crafts Fair, the highly coveted brassware and woven textiles have not only helped the Maranao community recover but also reconnect with their cultural identity. Among the community leaders is Salika Maguindanao and Jardin Samad, who’ve been working to preserve and elevate their craft for a better future for Maranao weavers. adobo magazine was able to catch up with the duo behind Maranao Collectibles on their journey since the siege, and the plans they’ve been weaving.

“The men have started to weave.”

This is what Salika Maguindanao, a young Maranao weaver and a Sultan’s daughter from Marawi, shared with me when we met two years ago. At the time, it had barely been a month since militants affiliated with the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant group attacked and sieged the city of Marawi in Mindanao, triggering five months of armed conflict with the Philippine military force. It was also barely a month since Salika and her family fled their home amid gunfire and bombs, along with so many others from her hometown. Her family had found safety and refuge in an empty convenience store in Iligan City, which would serve as their home for several months even after the war was over.

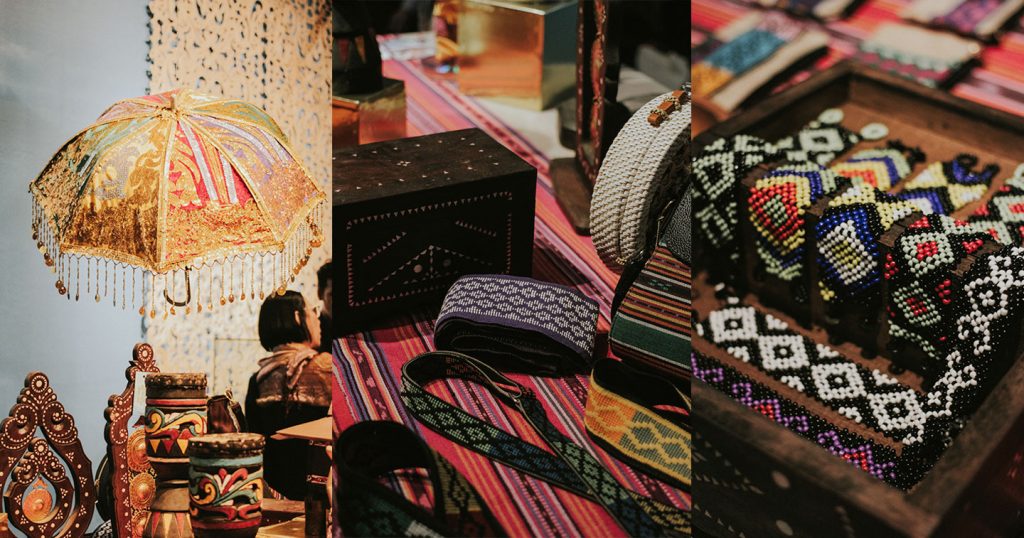

Anyone familiar with the customs and traditions of the Maranao people would understand that it is not at all the convention for men to get behind a loom and weave; traditionally, weaving is considered a woman’s activity or job, whereas the men undertake more rigorous and masculine endeavors (such as enlisting in the warrior workforce and defending their family/unit, for one). For a man to sit behind a loom and weave intricate patterns into fabric would not just be unusual, it might even be perceived as ridiculous. Thus, for Salika’s husband to resort to weaving as a means of getting by and earning a living had meant these were desperate times indeed. “We needed to earn more to be able to feed ourselves and our family,” Salika’s husband and business partner Jardin Samad explained, sharing that his printshop business simply wasn’t earning enough to make ends meet. Like many Maranao families, Salika’s is a craftmaking clan that took pride in their long tradition of weaving with backstrap looms to produce the traditional Maranao weave known as langkit. The langkit design is particularly distinct and lauded for the intricate geometric patterns referred locally as okir, and is typically fabricated into strips sewn into a tube-shaped garment commonly worn in Mindanao known as the landap or malong.

Coming from a high-born family, Salika and her sister learned their family’s age-old craft behind the loom from the family’s matriarchs since childhood, and witnessed the amount of work and time spent on producing a single piece. Watching their grandmother, their mother, and the women in their family had taught them the value of their woven products, as well as how profitable each woven piece of fabric is in the market. A 5- or 10-meter piece of landap could sell for thousands of pesos, depending on the intricacy of the langkit design. As with the brassware and the carved woodwork that hail from these communities, Maranao design aesthetic can be described as elaborate, ornate, and lavish. Traditional langkit designs have deeper and subdued colors such as maroon, purple, and blue with hints of yellow or white as compared to modern designs.

Amid the bombings and warfare that ensued in the broken streets of Marawi City, Jardin braved the chaos and returned to their home to recover her family’s looms and weaving tools. “We were all stranded in evacuation centers like that convenience store while money was running out, and we had to plan our lives during this uncertain time and not be helpless to circumstances and whatever the outcome of the war; no one had any idea when the war would end, or if we would even have a home to return to,” he shared as he recounted how he managed to sneak a vehicle through Marawi in the midst of the ongoing battle. “We needed to weave to be able to eat and get through today and see tomorrow. There’s no time or space for macho pride.”

At the time, Salika had found an opportunity to sell their products, as well as showcase her peoples’ craft and cultural identity while raising awareness about the war and the plight of the people of Marawi. With the help of a supportive network of contacts, Salika was able to join a textile and cultural trade expo in San Francisco, the Hinabi Project 2017, thus providing her both a market and a platform for her advocacy. As the ensuing war destroyed the homes and livelihoods of the Maranaos, it also exacerbated the issue of their dying traditions and craftwork in these modern times. In the last decade, the younger generation have shown decreasing interest in weaving, opting to pursue professional careers in the private sector or carve a different path outside their culture and their hometown. Beyond ensuring the survival of her family as Internally Displaced People (IDPs) amid conflict, Salika was also determined to preserve her people’s cultural identity and traditions.

It’s been two years since she and her husband made the journey to the United States to join the Hinabi Project expo, in the hope of selling their fabrics and ensuring a future for the weaving community back home. At this year’s Manila FAME and the Philippine Arts and Crafts Fair, hundreds of exhibitors filled the vast trade halls but it wasn’t impossible to catch the Maranao Collectibles booth and the vibrant langkit designs that were on display.

We have a lot to catch up on since we last spoke. Can you tell us about your experience in the US when you both joined The Hinabi Project expo in San Francisco?

Salika: We went to the US for the demo, and nahirapan kami to travel because there were doubts (understandably) on our intentions—if we would disappear and become illegal immigrants. But when we arrived, the reception was so warm. We felt so welcomed and we didn’t want to break the trust. We wanted to prove. It was there we felt the calling to continue our craft. When we were there, there were so many other indigenous communities representing their culture and crafts. I looked at them and saw they had so many other things. I looked at us and thought, why do we only have weaving? I know we (Maranao) have such a rich culture. So we thought, we really need to come back and help continue our traditions and culture of weaving. If we ever have a chance to come back, we want to prove ourselves and showcase what we are, how much we can do. We’ve been figuring out. We were given so many opportunities. I thought, I cannot just let this pass and not figure out how to preserve our culture, our people’s traditions. I thought, God, is this your way of showing me what my path is? As a survivor of the Marawi siege, we really need to give back.

Were you able to sell handwoven products during the expo?

Salika: Yes, we sold many products, and then after I applied for a social enterprise training like an ideation camp that would award grants (in Davao, for 10 days). The DTI pointed this opportunity for communities in Marawi to recover and rehabilitate. We went through mentoring and coaching on how to develop and run a social enterprise, and I figured this was the best path for us. Because we really do need to run a business and generate income, but we also need to help our community to recover while preserving our traditions and culture and this heritage craft. We also need to help create livelihoods and jobs for our community.

How are the efforts in reviving weaving in your community? In encouraging the men to weave?

Jardin: Yun talaga tinarget namin buhayin. Siempre maraming lalaki na ayaw, machismo. Para sa akin kasi, doon (sa pag hahabi) kami nakakain ng maayos, at nakatulong ng maayos. Before the war, printing lang yung hanap-buhay ko and kulang yun. Since the war, ako gumagawa ng looms at naghahabi din. Nakatulong talaga sa amin, and gusto ko rin ipakita sa ibang lalaki na hindi kailangan ipagkahiya ang lalaking naghahabi. Ang laki ng opportunity dito kasi. Walang dapat ipagkahiya; bakit sa ibang kultura, gaya sa India, naghahabi naman mga lalaki. Ewan ko ba kung dahil ba sa mga dating beliefs ba, na baka mashadong mataas para mag-habi. Pero wala naman sultan o hari sa gera; naranasan namin lahat nun. Pantay-pantay lang kaming lahat, lahat kami mga bakwit or IDPs, na tumakas sa gera. Pumila, humingi ng pagkain. Nag survive kami, natuto kami mag weave. Hindi nakakahiya mag weave.

Salika: Naisip rin niya na one way to convince other men is to make our enterprise successful. If we are able to prove that this model is sustainable and profitable, the others will follow suit. Somehow, dumami na ang mga weavers. Maraming nangangailangan ng trabaho kasi, and we want to give opportunities for livelihood. A lot of men are looking to us for jobs but feel ashamed about weaving, since it is traditionally taboo for men to weave. So we are looking at other options also, like constructing looms, and somehow that has been more feasible for me to do. For example, one of my cousins experienced rido (family feud wars) and had to flee and escape, and ngayon nakatago sila and figuring out how to survive. I told them to collect and wash coconut shells and I’ll buy them from them. I am still in the product development stage for these materials, but that motivates me to figure out how to help them earn some income in order to survive even if they are in hiding. There really are many ways to help and reach out, not just handing out monetary help, but figuring out entrepreneurial ways that can be sustainable for the community at large.

A thriving social enterprise

Salika: In addition to participating in expos and fairs, the most sustainable for us have been orders in bulk. As well as partnerships with other social enterprises (like Junk Knot) that really believe in helping the community so they understand the need for our community to earn and recover, and the value of our products. What really boomed for us was when we had an order to produce the medal ribbons for the 2018 Ironman Triathlon. [Author’s note: The Maranao langkit design was selected among 15 other weaves from various weaving communities all over the Philippines as collected by The Dream Project, a nonprofit organization based in Negros Occidental that works in enabling creative innovation and education in underprivileged communities.] The order was for 1,400 pieces and this was a real challenge for us because we had less workers and we were still trying to rebuild our lives and homes back in Marawi. But this was a great opportunity for us so we strived to make it work—and we did. Recently, we received an order to produce 3,700 medal ribbons for the UAAP. This time around we had learned from the Ironman experience and we have more workers on our team so it was more doable.

Weaving Dreams and a Sustainable Future

Salika: We are very fortunate that DTI and DOST helped us get equipment for so we can scale our work. My dream is to have a real operational textile factory in Marawi, so more people in the community can have jobs. So we can really increase our weaving capacity as weavers and producers, and we really want to build and sustain an industry for Marawi. I want to standardize the value of their labor and products. Unlike before, where it used to take so long before they could sell and earn. In the markets, the valuation for their products were lowered because of low demand, so they couldn’t sell and earn high. Now, I standardized the pricing, so it’s fair and they can earn money as soon as they finish producing.

The Youth and Preserving Cultural Traditions for the Next Generation

Salika: My concern also is that very little emphasis and attention is given to art here in the region (or at least in Lanao del Sur). Yes, you’ll find old artworks and examples of Maranao craftwork on display in museums but these are all old, like antique displays. There’s no real focus on new art, or new forms of creative expression for a younger community. There’s little opportunity for expression in schools. But now is the best opportunity, since we are all rebuilding and recovering. It’s also a medium to save the youth, to save them from violent extremism and vices so they can express themselves and have a creative outlet.

Photos by Jether Dane Guadalupe

About the contributor

Before hopping into the freelance world, Chiara helmed adobo’s editorial team as its Editorial Director and helped in the transition to a platform-agnostic content system. Previously, she was the Managing Editor of a travel publication and the Editor in Chief of a private banking magazine, as well as a UX Writer for apps and websites. She currently oscillates her writing time between longform features on art and heritage preservation, and making digital interfaces delightful to use with words.