In adobo magazine’s March-April 2011 issue, we featured New York-based graphic designer Lucille Tenazas, who wears her Filipino culture loud and proud. Here’s her story.

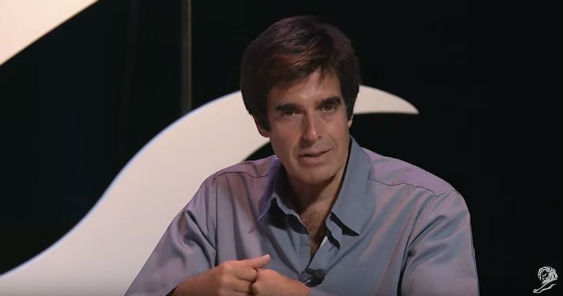

The lady speaks a thousand words and draws bold outlines with her fingers. As she narrates with every flick of a finger and a tap of her hand in the air, her humor cascades over her like a glass curtain – a revelation and an affirmation – of her inner bearing. Being one of the most respected graphic designers across the United States, Europe, and the Philippines, Lucille Tenazas wears her crown of glory proudly, and with occasional playfulness. Born in the Philippine province of Aklan to a civil engineer and a history teacher, Tenazas is proudly Filipino. Currently a Henry Wolf Professor in Communication Design at Parsons The New School for Design, she was also the Founding Chair of the MFA Program in Design at the California College of the Arts.

During her lecture at the Ayala Design Talks in February, she joked around her father’s undying love for mathematics. She flashed a grid on the screen – a play on letters using her family members’ seven-letter first names and their last name. Tenazas walks into her high school reunion only to realize that she was the only one with naturally white hair. A simple facet that explains Tenazas’ work in all its simplicity and stark is that she lets her work flow through her pen – tablet or ballpoint – in clean lines, astounding types, and bright colors that bring her work a notch up every single time. It was never easy, she says. After completing her course in Fine Arts at the College of the Holy Spirit in the 1970’s, graphic design was still not something people would normally venture into. Admittedly, Tenazas’ career began with pencils, ballpoints – she did not enjoy fat materials to draw with. She gravitated towards advertising which she found to be the closest she can get to copywriting, poster and graphic design. But magazines that featured design always sat between her bookends. Flipping through the pages of these magazines, Tenazas was inspired by design works of Milton Glaser and Linchpin Studios. It was not until she found out that graphic design courses were available in most of the good schools in California that she decided to dive in and take another undergraduate course. She took her second undergraduate degree at the California College of Arts and Crafts (CCAC) in San Francisco, under the mentorship of April Greiman and two stalwarts in design: Michael Manwaring and Michael Vanderbyl. During her stint at CCAC, she was able to build a portfolio impressive enough to get her into Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan (where Philippine national artists Napoleon Abueva and Jose Joya studied) where she completed her Masters in Fine Arts.

At Cranbrook, she would usually sit at the back of the room being a keen observer. “I was always interested in seeing how people confront new situations,” she

says, and goes on by sharing what she tells students about being cultural nomads. She continues, “A cultural nomad absorbs what’s going on. A cultural tourist stands apart. That’s why you know they’re tourists… I also felt that. This is a life story, a life lesson. When confronted with a new situation, we as designers think, how do we get taken seriously, how do we fit in the situation?” Fortunately, fitting in did not come as a difficult feat. Her professors would always notice her work during

rounds, stand a little bit longer than usual beside her desk, and use her output as examples in class. Tenazas adds that her “projects are geared towards the culture. I see myself as a visitor but I also want to gain the experience of working with students of that culture.” Which, perhaps, influenced her desire to hone young talent and create a diverse pool of eager minds. Her passion lies beyond what she does. Being able to experience and be at the center of a design rebirth in the United States fueled her to absorb the eminent change from the West to the East Coasts. New York, at that time, was thought to be the center of everything new. She was just happy to be there at the time when Texas, San Francisco, the Northwest and Southeast states were already holding regional design competitions.

Before setting up her own studio, she fondly recalls her humble beginnings in a small design firm wherein she cranked the work day in and day out. “We got this visibility without me knowing. I was in the back room, working away and I didn’t realize my bosses were getting all these compliments,” she says. And to have her bosses assert her design to the clients whenever they wanted to change the design was one thing she did not expect. She shares that one of her bosses was in a meeting one day and just as he presented Tenazas’ design, he quickly ended it with, “Lucille worked on this a long time and she really thought this through. So listen, you can’t change it.”

That is the balance she learned from osmosis – to pick up the things she does at some point in her career that will be useful in the future. “Take the job and learn from it, but you have to know when to leave. While you’re young, you can still be portable, do it.” To be portable entails being able to keep up with the times. With the design surge came the emergence of Silicon Valley in California and New York, it was inevitable for manual cut-and-paste to take its final bow.

Although Tenazas explains how computers made work more frivolous and the turn around was faster, she takes pride in being trained back when the work was done slowly and more purposefully. But she also considers the advantages of having newer tools as a mode in which to create more output.

“Before, I would make three sketches, but with the computer I will make 20, which I extracted from the three.” Tenazas then shows her notebook filled with sketches. “I sketch a lot of things. I don’t design on a computer…. nothing comes out of my office that I have not approved.”

As a designer, it is one thing to pay attention to detail and another to be a perfectionist. “You have to allow for some irregularity. I pay attention to detail, even if the detail is the imperfect detail. Like the Shakers. In their quilts, for example, they purposely discolored, put an extra stitch. In their mind, only God is perfect… I like that.”

Tenazas treats her work as a mind game. “You don’t have to give everything away. You give enough clues and let them fill in the blanks,” she says. “Give them a chance to figure it out. I give clues and the interpretations are as varied as the people who look at them and I think that requires a certain trust.” This certain philosophy and zeal in her craft have gained her numerous recognitions such as the National Design Award for Communication Design by the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum of New York in 2002. She was American Institute of Graphic Arts’ national president from 1996 to 1998 and was given a place in I.D. Magazine’s I.D. Forty of America’s leading design innovators in 1995.

Her works transcend convention, that’s a fact. So when asked about a project she has been wanting to work on, she quickly answers: “A dictionary. Something that, for centuries, is based on a conventional way of looking at something. I want to do something where you can break convention in a way that is much more without doing it for the sake of changing it. Dictionary, there’s a convention. There are tabs.”

On repeating work, Tenazas shares that “If you’re always using white, use black. If you’re always using vertical, use horizontal. Go the exact opposite of what

you normally do…” To try and bring back something almost obsolete from an analog world is a challenge to take on by the reins. “At the end of the day, it’s me and myself. Life’s too short to do boring things,” she says.

Words: Kiten Capili

Photograph: Abby Yao