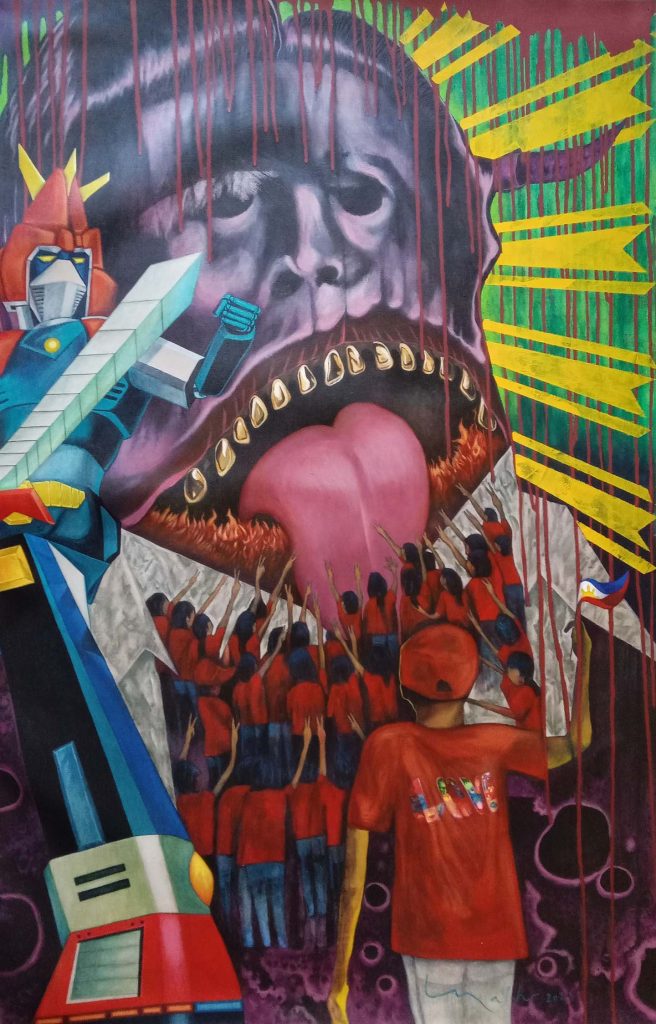

MANILA, PHILIPPINES — When the horn-headed aliens from planet Boazan invade to conquer Earth, a team of young heroes goes “Let’s volt in!” and turns into Voltes V to save the day. Pilots of five attack vehicles fly into a V formation, and using ultra-electromagnetic energy, they come together to boost their strength to fight the superior Boazanians. This mind-blowing transformation into a Super Electromagnetic Machine that kept its young viewers glued to their screens happens with the LSS-inducing theme song in the background and the all-too-familiar battle cry, “Voltes Fiiiive-vah!”

The recent return of Voltes V on mainstream TV banks on the power of nostalgia over the beloved Japanese anime, particularly among its first Filipino viewers whose excitement for its nearing finale was cut short by the banning of the show in 1979 for promoting “unwholesome attitudes among children toward violence,” but the show’s fanatics swear the story of Voltes V promotes good values with the heroes looking for their missing father, the underdogs standing up against injustice, tyranny and oppression, and the five pilots learning the value of teamwork. For many, Voltes V is really about “family and freedom.”

The V in this iconic anime character stands for the five heroes, and presumably their ultimate goal —Victory. Coincidentally, the rebirth of the popular “peace sign” during the last presidential campaign resembles the letter V, with the candidates waving it ending up victorious indeed. Perhaps more than any other political party, the current officials put a premium on the impact of images and the power of propaganda. More than a year into the “New Philippines” regime, and upon lifting the country’s state of emergency from the Covid-19 pandemic, logo launching became a regular event. Government agencies have been promoting their redesigned logos left and right as part of the administration’s campaign for a new brand of governance and leadership. Bagong Pilipinas is “characterized by a principled, accountable and dependable government reinforced by unified institutions of society,” and it comes with its own logo.

Logos, after all, are graphics for easy recall and understanding of what a brand is all about. The design is as important as the capacity of the brand to make good on its commitment to its audience. When a government, or any organization, cannot deliver on its brand promise, then the logo means nothing. There is a fine line between branding and propaganda. Branding happens when a word, a slogan, an image, or a logo is repeatedly projected to the public until it remains firmly in their memory, and they finally take it for a fact. Political branding involves government and political actors and can be used for either public information or mass disinformation. The success of political branding or campaigns to instill ideas aimed at shaping public opinions has been most evident in the past national elections. An entire nation suffering from “truth decay” has been voting based on its perceived facts. As one Madam once pointed out, “Perception is real, the truth is not.”

Amid all the brouhaha over the strongly criticized government logos and campaigns, Bagong Pilipinas has been marked by high inflation rates, high prices of basic commodities, high unemployment rates, and low expectations from incumbent leaders. 51% of the Filipino families who rated themselves “poor.” and even the 30% who considered themselves on “borderline,” are bearing the brunt of poor public service delivery, problematic education system, tensions in the West Philippine Sea, damages due to extreme weather changes, red-tagging, and mounting cases of massive corruption. With hope running dry, most Filipinos, particularly those without privilege or power, are turning yet again to their most available source of strength, their faith. Some would argue that in “faith, hope, and love,” the greatest of all is faith.

Faithful Filipinos can be followers of superpowers or local heroes, saints or deities, prayers or rituals, religious articles or amulets, influencers or idols, political parties or patronage, vaccines or facemasks, Lazada or Shopee. Faith in the protection and power offered by these fountains of hope is a comfort provider to overcome challenges, as well as a courage booster to make things happen. Faith is a formidable force, the vaccine to a virus, the booster to a weakening immunity, the Voltes V to Prince Zardoz. Faith is hoping for heroes’ timely rescue, the prayer to one’s god for protection, the undying quest for mystical powers, the rain dance to water shortage, the dopamine from fangirling K-Pop idols or binge-watching K-Dramas, and the highly sought-after assurance from political alliances.

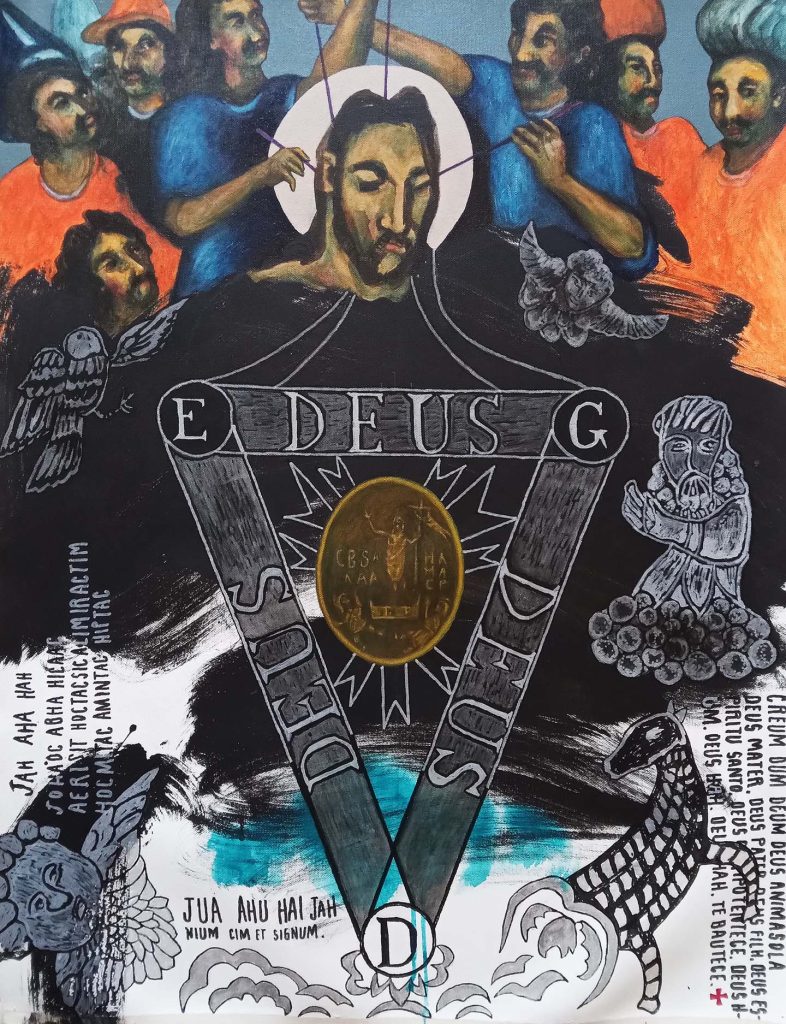

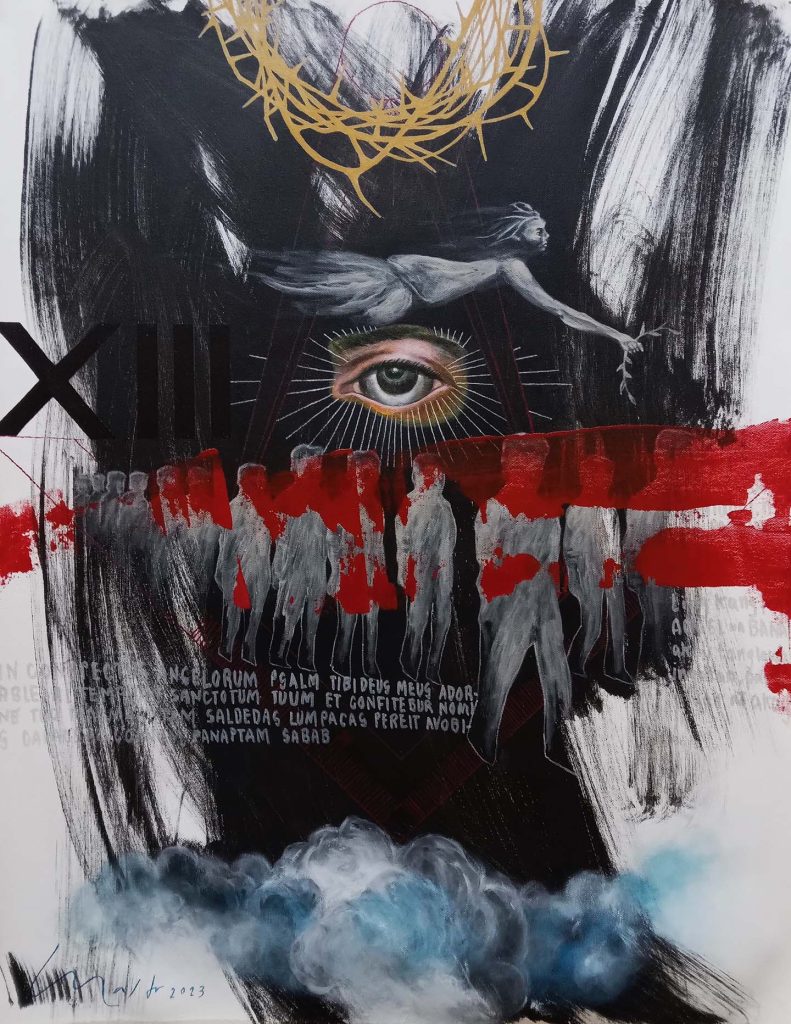

In his painting exhibit, Bisa artist and University of the Philippines Fine Arts professor and painter Marco Ruben Malto II examines the efficacy, influence, power, or strength of various forms of faith. This is not the first time Malto has featured manifestations of the Filipino faith in his works. Faith and the beliefs that they represent using the enigmatic anting-anting elements is a recurring theme in the artist’s works, alongside his suggestive narratives referencing popular images to reflect on current issues dominating the nation. The symbols found in anting-antings can be traced to hybrid beliefs combining Roman-Judeo-Christian religion and Filipino folk beliefs in the Bathala. Just as each element in a logo design is strategically decided to achieve desired results, the symbols etched in the amulets are meticulously composed in order to heal, protect, and strengthen the faithful wearer. In Bisa, the artist showcases how every text in pidgin Latin deliberately inscribed in his works is interplayed with imageries to put to power what many Filipinos consider their talisman.

Marco’s Bisa Exhibit opens October 14, 6:00 pm, on the 2nd floor, Boston Gallery at 72 Boston Street, Cubao, Quezon City. The exhibit runs until October 31. Gallery hours are from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm, Tuesdays to Sundays.