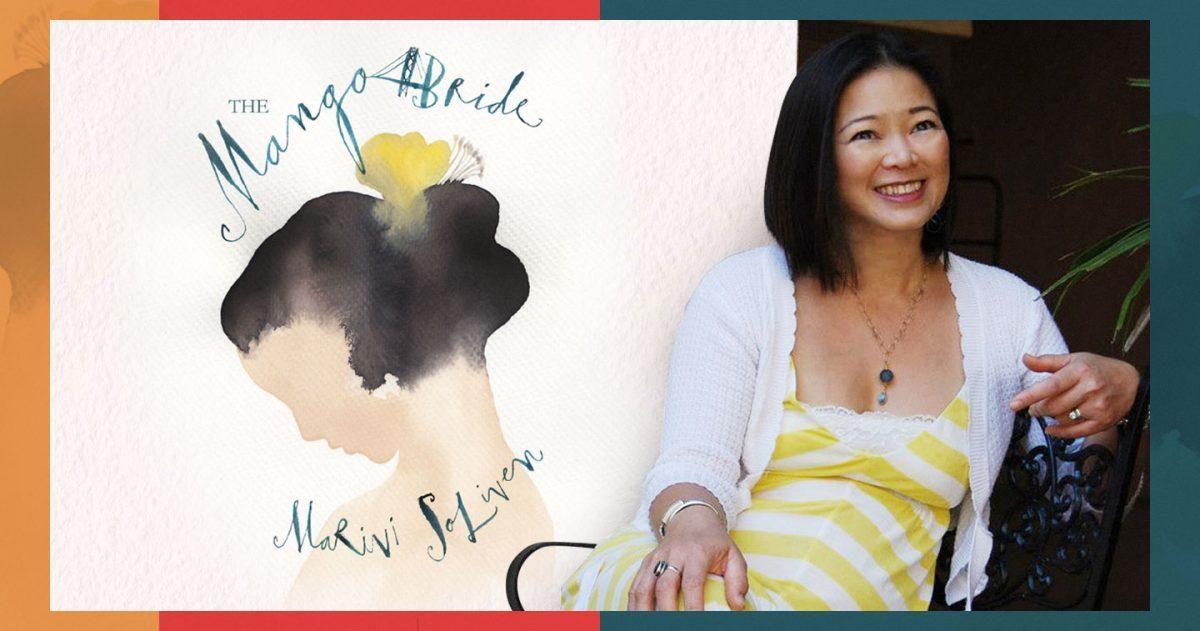

MANILA, PHILIPPINES — When Marivi Soliven put to paper her award-winning novel The Mango Bride in the year 2008, she never considered that, one day, she’d get to see the story come to life on the big screen. She was just writing a story she thought needed to be told. Fast-forward to a decade later, the book is sold out everywhere and prices are shooting up after the big news broke: The Mango Bride is getting a film adaptation, and with Filipino megastar Sharon Cuneta billing the lead role, no less.

With Filipino-Canadian director Martin Edralin at the helm and Filipino filmmaker Rae Red penning the script, Soliven’s powerful narrative about immigrant women will reach a huge audience. The story of Amparo Guerrero and Beverly Obejas — the main characters in this compelling tale exploring the two sides of the Filipino diaspora — is close to Soliven’s heart. Since the book was published in 2013, supporting Filipino immigrant survivors of domestic violence has become her advocacy.

In this exclusive interview, adobo Magazine sat down with Soliven to talk about the process of writing The Mango Bride, what she hopes the film adaptation will get right, and how the heart of the story is a powerful message about women.

First of all, congratulations! This adaptation is such an exciting thing. When you were first writing the book, did you imagine you would see the story come to life on the big screen?

No, I didn’t even think it would be published. [Back then] Taryn Fagerness, a literary agent at the Sandra Dijkstra had read Spooky Mo, a collection of horror stories Milflores Publishing was on the verge of releasing. She liked it so much that she asked if she could offer me literary representation for the book. And at the time, the senior agent said, “No, she has to start with a novel.” I came so close, I thought.

I joined National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) because I was determined to get published, just to get over the fear of writing in the longform. I was an ad copywriter, I wrote flash fiction, and the longest thing I’d ever written was maybe 4000 words. After drafting a 50,000 word novel at NaNoWriMo, I spent two years polishing it. At the end of those two years, I went back to that same agent, and I said: “Two years ago, you asked me if I had a novel. I didn’t then, but I do now.”

Can you give us an idea of how you finally got to this film deal and how long it’s been in the works?

This deal has probably been in the works since last April, so [it moved] pretty fast. But before that, I had waited since the book was launched in 2013 for something to come together with a different production company. In the meantime, several independent filmmakers approached me. Even though I had these other offers, I chose to stick with the larger company that had first offered me this deal, and I waited and I waited but nothing happened.

I finally decided I was done waiting when a friend of mine [told me] that in the United States, they actually pay for that option, which is basically like good money down, a sort of reservation, or contract that for a set amount of time, usually 2 years, you will not sell the option to another film company. At the time, I didn’t know that options were paid for. By 2019, I was talking to my sister who is a lawyer, and I asked her to look at the contract. We realized it had been with the other company for 18 months and not signed. So I withdrew. And [with that] I thought, “I’m giving up on the dream.”

Then last year, my former literary agent forwarded me this weird email that was like, “Hey, I’m Micah, I want to help! I want to turn your book into a film.” I’m thinking sure, I’ve heard that before. I didn’t believe her! But we set up a Zoom meeting. Over time, she convinced me that she was serious, and this time there was money on the table. Now, with Micah Tadena of 108 Media, I would say we have met on the average of at least once a month, at least, since April. She has been very proactive about moving the project forward. For that, I am very grateful.

She organized a four-country meeting yesterday to introduce the full team to each other — the director in Toronto, producers in Los Angeles and Singapore, me in San Diego, and she and the screenwriter in Manila — four countries and three time zones, but she made it happen.

So, when you first got this deal or like when you first realized that this was really pushing through, what was your first reaction? Did you have any apprehensions at all?

I was cautiously optimistic, because you understand I had six years of waiting for nothing. I wanted to see what would happen next. But there was always a next step that Michah offered, which I really appreciated.

Are there any nuances in particular that you’re already considering will be important to get right, moving from a written medium to a visual one?

The concept of class differences in the Philippines is very important to the novel, because it really does determine how the two main characters experience immigration in the United States. It kind of narrows their expectations and whatever they came from informs what they will have moving forward. They need to get [the concept of] class correctly.

There are certain markers of class: there’s a certain way of talking, you know, the conyo kids, the way they talk — the way they mangle English is very different from the way lower middle class Filipinos mangle English. It’s a different kind of Taglish. And I’m not casting aspersions on either class, I’m just saying it’s different, like the difference between an East Coast accent and a Southern accent in the United States. You can tell immediately, by the way they speak that they are from different places. So, language will be crucial.

Martin Edralin is set to helm the film adaptation and Rae Red will be penning the screenplay. How important is it to you that the people behind the scenes are Filipino? Do you think there are certain sensibilities in your story that only Filipinos can properly portray?

Oh, absolutely. I had a long discussion with Micah about this. I’m glad we were on the same page. At the very least, the director had to be Asian; ideally, Filipino.

The concept of shame is very strong in the Philippines. The concept of wala kang hiya or wala kang pinanggalingan, wala kang pinag-aralan. All of that, it’s almost in our subconscious. It’s so strong that you’re almost born with it. If you didn’t have a Filipino director who understood that sensibility, it would be really, really hard to educate a foreign director into showing how that manifests. I thought it was important to respect the culture [in this way]. When I saw Martin Edralin’s film Islands, I knew he understood. He gets it and obviously Rae Red gets it, and they make a really good team. I’m really happy that both of them agreed to work on the project.

The Mango Bride is very close to your heart, not just because it’s a novel that you worked really hard on, but also because it’s tied to advocacies you’re passionate about. Can you paint us a picture of how this story has supported these movements in the years since it was published?

My day job is phone interpreting. Everyday I’m in touch with the Filipino immigrant community. I hear their stories by way of the calls that I take for them. When I was writing the novel in 2008, there was the subprime mortgage crisis — people were overextending themselves with loans for houses that they couldn’t afford, going bankrupt and becoming homeless. It was a huge crisis. When that happened, the economy sank, and I began to notice a sharp increase in calls that came in relating to domestic violence.

When I asked the social worker why that was, she said, “Well, that’s typical.” Anytime there’s any kind of economic catastrophe or even a national natural disaster, domestic violence rates will soar. Men tend to be disgruntled if they’re laid off or furloughed or their pays cut. And they tend to take it out on the person nearest to them. That’s usually the wife.

Because I was a Filipino interpreter I was interpreting for Filipinos who were… I wouldn’t say they were all mail-order brides, but there were definitely immigrant brides. A lot of them didn’t understand the system. This is another way the concept of shame comes in, you know — the Philippines is the only country other than the Vatican with no divorce. There is no second act for a bad marriage. These women who have married foreigners and moved to another country, they know that there is no going back; they will never marry again. So they suck it up. The situation becomes really dire because in the Philippines, you don’t wash your dirty laundry in public. And [then there is] this stupid Catholic idea that God only gives you the cross that you can bear to carry. That’s what Filipinos are raised to believe. So these women will suck it up until they’re at the point of death. And that’s usually when I come in. When they’re being interviewed to enter a women’s shelter, or they’re being assessed for psychological damage, or they’re filing a police report.

Around the same time, immigration was starting to heat up. I thought, well, this is a story that needs to be told. There is a domestic violence issue in the immigrant community. On the other side, there are Filipinos who left better places or positions in the Philippines to move on, to have to do their own housework in the United States. God forbid they have to do their own laundry, but they do because in the United States, there are no house helpers. And they came here for whatever reason, to marry. In my case, I came here because I was marrying my husband, because we loved each other. But other Filipinos come here to do medical residency, to accept higher paying jobs, to pursue graduate degrees, for many reasons. A lot of them leave better lifestyles in the Philippines for a life in the United States starting out without a network of family or friends.

I wanted to show two sides of the immigration coin. It was important for me to juxtapose those so that the greater American public [learns about it], even though I wasn’t writing for them. It’s not just “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore” (The New Colossus, by Emma Lazarus).

Immigration changes you on a granular level. You have to remake yourself when you move yourself, your physical self, to a foreign country where you may not speak the language and that may have institutions that you do not relate to. It’s a huge change. I wanted to capture that in the novel.

The novel was published in 2013. You were also in a very different place back then. Do you ever reread your book now and again? And does it feel like the meaning of the book has evolved for you in any way since 2013?

When I wrote the book initially, I just thought it was a story. That’s the end of it. Then after the book came out, a funny thing happened: All of these women started to write to me. Even my high school classmates would write to me, and one of them was like, “When I got to that part where something terrible happens, I started to cry, because that happened to a relative of mine.” People I didn’t know would write to me, they would find my email address and say:”Hey, you know, that thing that happened to this one character? I lived through that.”

Over time, I thought, maybe the universe was telling me I needed to do something about domestic violence. I looked for a nonprofit, in San Diego where I live, that offers aid to immigrant survivors of domestic violence. It had to be immigrant survivors, because I think immigrant women are at a much greater disadvantage. We don’t depend on social services, [same as] in the Philippines. You know, asa ka lang naman sa pamilya mo o sa kaibigan mo, but you’re not going to go to the social worker; it’s unheard of. It’s a big problem for domestic violence survivors. When they come here, the only contact to the greater American world are their husbands.

I found a non-profit called Access Inc. whose legal aid director and multistore is a Filipino American. I asked her, how much does it take to save one immigrant survivor of domestic violence and gain her residency under the U Visa? About 800 USD, she said. We can do that, I thought.

I called in all my favors to bring in items for a silent auction: I asked my then literary agent to offer to critique the first ten pages of someone’s novel, I asked my daughter’s violin teacher to offer a private performance favors, I donated copies of my books. Susan McBeth of Adventures by the Books helped us organize a dinner at the Joan Kroc Center for Peace and Justice at the University of San Diego and former United States Ambassador to the Philippines Harry K. Thomas Jr. drove in from Arizona and gave the keynote speech.

I just remember that I was so stressed out in the weeks leading up to the fundraiser because I thought we would not raise enough money that four days before the event, I contracted shingles. But we were able to raise over 9,000 USD. We saved nine immigrant survivors of domestic violence from their abusive relationships, and those women now have legal residency and they are no longer with their abusers. So to answer your question in a very long-winded way, I think that’s what the book turned into — it became my advocacy. I will go anywhere if someone wants me to speak and help them raise money for nonprofit organizations that help immigrant survivors of domestic violence.

It’s amazing, and I’m glad that you mentioned these people reaching out to you because a lot of your readers found themselves in the Mango Bride. Now that the movie is going to reach an even wider audience, are you hoping for more [of the same]?

I would hope so. A movie is entertainment. But I think that if you watch the movie, or if you read the book, you will have a way to give words to whatever you’re experiencing, or whatever your friend or your mother or relative is experiencing. You can talk around that. Then it opens a safe space to talk about things. If the movie serves as a vehicle to open up a discussion about domestic violence, then I think it will have served its purpose.

Even just with the news of the adaptation, your book is now sold out and you even talked about how the prices shot. Is there a reprint happening soon, do you think?

Hopefully, yeah. I’m working on reissuing a Kindle edition. I’m just waiting for the book designer to come up with the new cover design, because I can’t use the one from Penguin Random House. They gave me back all my rights, but when they did that, they also took their Kindle edition off, because that design obviously belongs to them. And they stopped printing the copies. I’m still kicking myself for not buying more copies before the movie was announced because the last price I saw on Amazon was for something crazy, like 183 USD for a secondhand copy.

The Mango Bride is really a book about Filipino women at its heart. What do you hope this movie will say about them or say to them?

It’s an odd irony that the Philippines is a matriarchal society. Women rule the house and traditionally run the finances in it. But certain sections of the law render us powerless. You know, if you leave your husband you become a separada, usually with no right to demand alimony or child support. That’s a paradox of Philippine society. We have so much emotional power, and we have so much influence over our familial sphere. But according to the law, and under the Catholic Church, we are almost completely powerless, and that needs to change.