“I suppose it makes me think of a carousel, going round and round.”

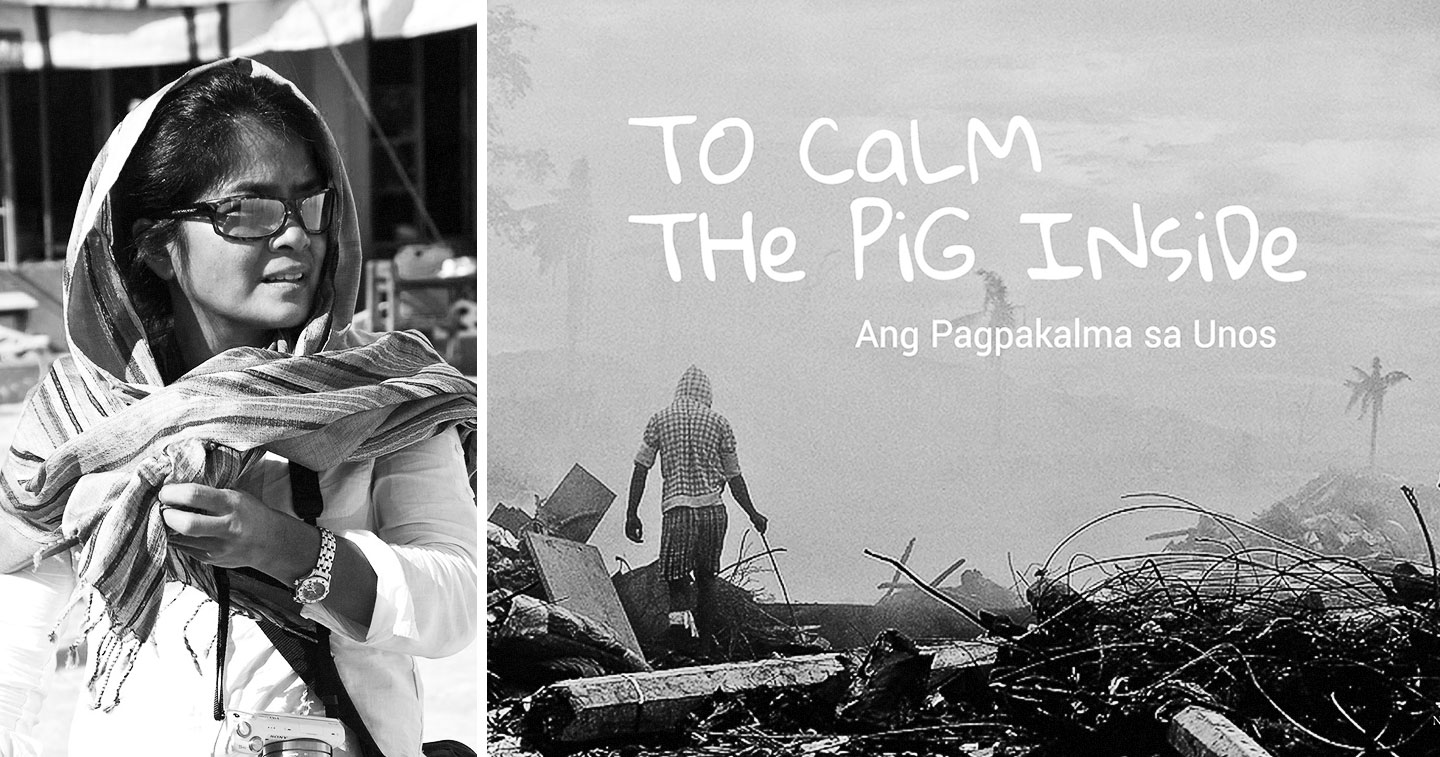

– Joanna Vasquez Arong director behind the award-winning documentary, To Calm the Pig Inside.

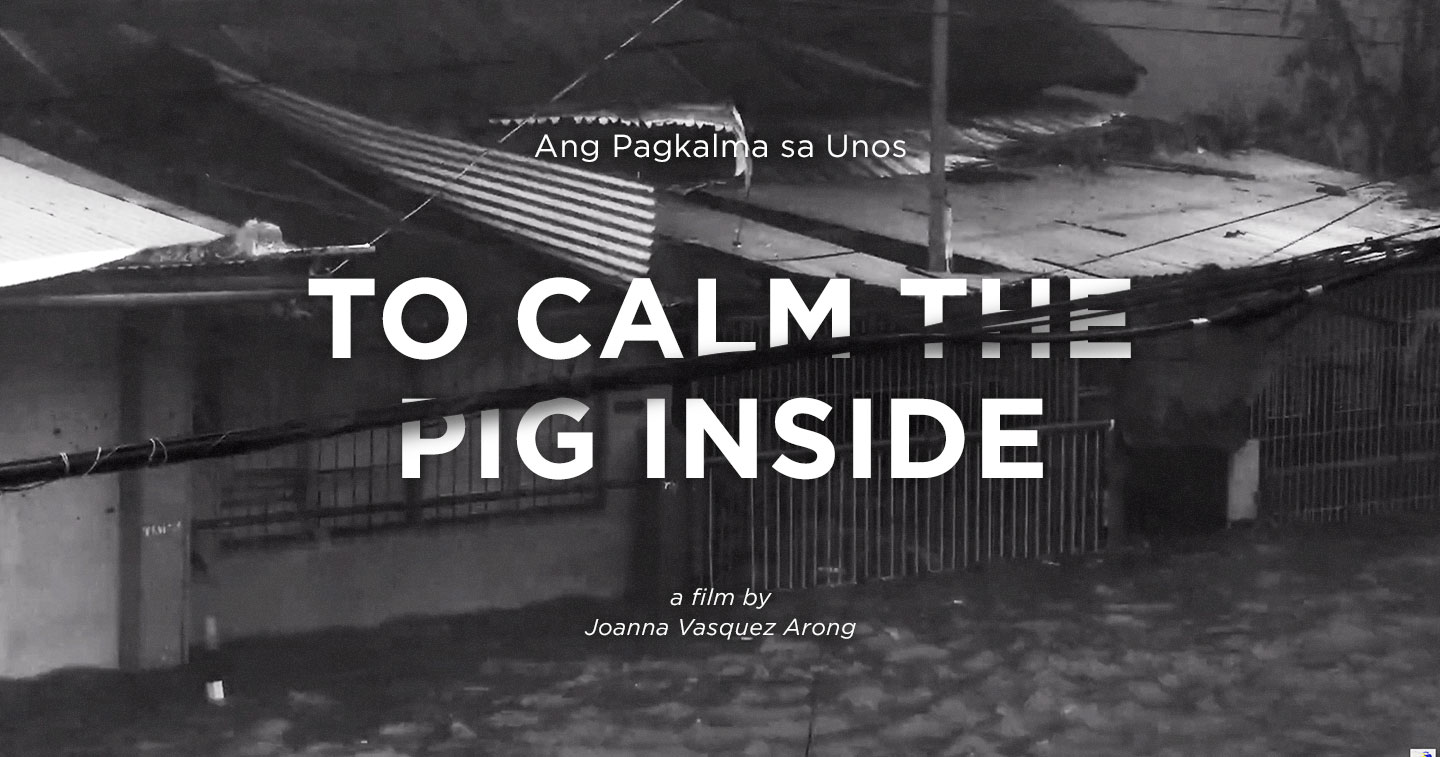

MANILA, PHILIPPINES– As I write this, Joanna Vasquez Arong’s Filipino short documentary To Calm the Pig Inside (Ang Pagkalma Sa Unos), which saw its world premiere during the 2020 Slamdance Film Festival last February, had just added another accolade to its string of recent honors: The Documentary Short Film Award at the Hawai’i International Film Festival (HIFF), which is focused on international cinematic achievement in the Asia-Pacific region.

Shot in black and white and running at 19 minutes long, To Calm the Pig Inside is described by the filmmaker as “a contemplation on the effects a typhoon leaves on a seaside city” where “myths are woven in to try to understand how people cope with the devastation and drama.” Besting some 54 other eligible shorts in the HIFF, this is on top of receiving the Special Jury Prize in the 2020 Cinemalaya Film Festival, Best International Documentary prize at the 15th Shorts Mexico Festival Internacional de Cortometrajes de Mexico, and special mention at the Bangkok ASEAN Film Festival 2020.

In her director’s statement, Arong recounts that after spending weeks line producing for a film production on the devastation super typhoon wreaked around the Philippines in 2013-2014, “I felt there was another layer to the stories which had not been shared.” Locals then began recounting to her their reflections, disappointments, dreams and even jokes they shared with each other in order to cope with the trauma.

She admits at first, however, that coming from a neighboring island, “it was not really my story to tell.” Thus, she decided to approach this story as a personal film essay that interweaves Arong’s own experience with stories gathered from the community at large.

That a documentary on super typhoon Haiyan and how it ravaged Tacloban in 2013—told through the poignant recollections a girl we don’t see but only hear—should be released at a time when another recent devastating typhoon, Ulysses, wreaked havoc to parts of our country just some seven short years later, seems upsettingly prescient.

And as world continues to battle a raging global pandemic that has turned our lives upside down; as Rizal, Bicol, Cagayan, and other typhoon affected areas in the Philippines arduously work at getting back on their feet; as economic uncertainty still lingers in the air, we caught up with Joanna Vasquez Arong to probe deeper into To Calm the Pig Inside and to get her thoughts on the present state of affairs and the state of the film industry in time of COVID-19.

The following are excerpts from an e-mail interview and was edited for brevity.

What was your impetus/motivation for doing a documentary on Yolanda?

Back in 2013, I was working on the development of my first feature narrative film, ‘The Sigbin Chronicles,’ and on the day Yolanda struck, I was scheduled to fly to France to pitch that film. I had been closely watching the storm as just three weeks prior, an earthquake devastated the neighboring island of Bohol, which also affected us in Cebu, and it first seemed like Yolanda was coming straight towards the same areas where the earthquake struck.

I had volunteered in Bohol, and was disappointed in the politicking that was taking place over the distribution of the relief goods, despite the desperation of the people. And I recall wondering how people would recover if this super typhoon hit them as well. My flight to France was rescheduled for the day after the typhoon, and since there was practically a blackout during the day of the typhoon, I didn’t see the devastation Yolanda brought about until I was about to board my plane. The images haunted me, and as soon as I arrived at my hotel in France, I was glued to the TV, incredulous and angry.

I was in Paris for the month after my pitch, and every day, I coordinated with friends in Cebu, trying to connect people in helping with the relief efforts, even from afar. It was a horrendous situation, yet it was also inspiring to see that every single one of my friends it seemed, was involved in the relief efforts. I personally thought it was partly because that could have easily been us, as our city was in the original trajectory of Yolanda. And even in Paris, I was really moved to see posters plastered all over the metro and bus stops “Solidarité Philippines.”

As fate would have it, it was in Paris where I ended up meeting a producer who was looking for a Philippine producer to help his team film the aftermath of Yolanda. As soon as I returned home, I coordinated with my network of friends, including those I volunteered with in Bohol, to help with the logistics with the shoot, as it wasn’t easy getting the basics after the storm, such as housing and food.

You’ve taken a non-traditional approach in doing this documentary, that is without the usual talking heads and so forth. Why did you decide on this approach?

This is perhaps my fourth documentary now, and I generally try to avoid talking heads. Even in my very short films, there are barely any talking heads, if ever.

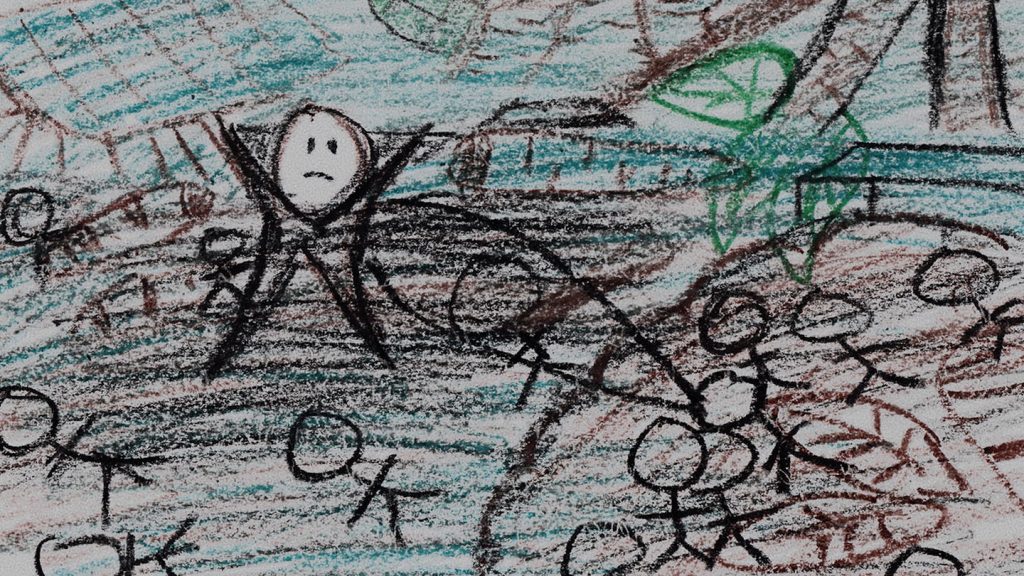

With this particular film, I decided to make it an essay film, to make it more a film about the collective experience. I felt there was no need to cite particular names for instance, and so therefore there was no need to interview people formally on camera. It was more about evoking the emotions or mood of the story being recounted via voice-over.

We noticed that the English title of the documentary is not a direct translation of the Tagalog title. Why is that?

The English title is actually closer to the heart or essence of the film. As narrated in the film, we had come across this legend of “buwa,” a pig inside the earth, and when agitated causes earthquakes, and people needed to calm the pig inside when the earth trembled.

I worked with two-three Cebuanos in translating the film, as I wanted to ensure the Cebuano translation was as close to the essence of the English version as possible, as I originally wrote the script in English. And we had come up with the English title of the film first. All of them felt that a literal translation of the title in Cebuano didn’t seem to capture the dual meaning of the title in English. So, we opted for a more poetic word for storm, “unos.”

Interestingly enough, when we translated the title into Spanish and French, I was also told that the better translation is similar to the Cebuano title, “Calmando la tormenta” and “Calmer la tempête.” Who would have thought that the notion of the pig doesn’t translate as well in other languages?

Have you returned to Leyte since then?

I had committed to starting a scholarship initiative, Eskwela Haiyan, for some children traumatized by Yolanda, so every year for the last seven years, I had gone at least once or twice, to visit our partners and students in both Tacloban and Guiuan. It’s a shame we weren’t able to visit this year due to the pandemic, as we had our last set of students graduate, and we were planning on holding a party in both Tacloban and Guiuan. Perhaps in the future.

I am still in touch with a few of the students, and continue to serve as their unofficial mentor. I continue to have big dreams for them.

The black and white photos you used were very powerful and moving. How was the process like in selecting the images to be used?

I was fortunate to meet two talented photojournalists, Veejay Villafranca and Piyavit Thongsa-ard, who were open to collaborating with me on this film. So, we had a lot more powerful and sensitive photos to choose from. In the end, together with our editors Lawrence S. Ang and Pao Sancho-Dalisay, we chose the photographs we felt expressed the story or emotion the most, lingering on the images, rather than showing too many photos.

The problems facing our country, more of the same, never seem to end, just as natural calamities like the recent typhoon Ulysses (which is like Yolanda all over again) continue to ravage our country. How does that make you feel?

It felt serendipitous that our film finally came out this year 2020 with the pandemic and the successive violent typhoons in the last month. At times I feel it’s easier to look at events in the past to better relate to our present reality. And again, when the successive typhoons hit last month, the politicking also was very familiar I suppose it makes me think of a carousel, going round and round.

You have a political science degree and a post-graduate degree in Development & Environmental studies. What led you to documentary filmmaking?

I have always been interested in photography and film, and in fact in college and during my Master’s I used to take photos for events. And I recall in college, whenever I had the chance, I would sneak to our library and just devour as many foreign films as I could. I also interned in a photo gallery then. I didn’t know any working artists, and coming from a family of professionals, I thought it was more prudent to follow a career in diplomacy, law or economics.

I thoroughly enjoyed all of my internships and work in international organizations and finance around the world; however, I was never really passionate about the work. I recall those days like it was yesterday; but it took me a while to finally make the jump in careers. During my transition period, I worked with Probe Productions in Manila to learn the basics of production. I feel that my background and interest in politics, development and environment continue to live in my films.

What role do you think can filmmakers play in causing societal change?

There are so many different types of films, and I feel film can sometimes act as a mirror to society, regardless of the genre, whether fiction or documentary, and can help people reflect on life. So, when films are able to move people, and even push them to reconsider their choices, it certainly becomes a powerful medium.

What reaction do you want to elicit from foreign audiences when they see To Calm the Pig Inside?

I don’t distinguish when making films, whether it’s for a foreign or local audience. I only make one film, from my personal viewpoint. And I try to recount stories so viewers can empathize with the characters, and hopefully transport them into the world and settings I’m recounting.

What can you say to cynics who feel that nothing is going to change with our country and its leadership?

I am very grateful for those who continue to fight to get the different dissenting voices heard despite the uphill struggle, and despite the seeming futility of the situation. We seem to be facing Goliath, but it inspires and leaves us with hope when we hear the Davids out there, and when we hear of the outpouring support for them, despite the risk.

With regards to film on our own reality back home, I do hope more people can see Ramona Diaz’s film, ‘A Thousand Cuts’ and Alyx Ayn Arumpac’s ‘Aswang,’ two important and courageous films on the present state of our country.

What do awards and recognition mean to you? How do you feel about the recent accolades To Calm the Pig Inside has received so far?

Winning the Grand Jury award at our world premiere was certainly the icing on the cake. Significant icing, as this prompted more people and festivals to become more curious about the film, and therefore our story on Yolanda started reaching an even wider audience.

It is a privilege to be granted this platform of screening in film festivals to share the experience of the victims of Yolanda. I feel their stories are somehow resonating, and perhaps the awards validate this.

At this very moment, I’m very happy to share that we’re one of ten nominees for the short documentary category for the IDA Documentary awards in the US, and voting is taking place this month until January 8th. It feels a bit surreal to be part of such a distinguished list of global filmmakers and films, and I even have to pinch myself. I chuckle as well as our film seems to be the only one that lists both the English and foreign title. It makes me happy and proud to see our Philippine title on this list. [you can visit https://www.documentary.org/awards2020]

What’s next for you?

During the pandemic, I’ve started considering how we’re going to feasibly shoot our next film, ‘116B University Avenue, Rangoon.’ This past fall, we were supposed to shoot our main protagonist, a Burmese writer in exile as she returned to Myanmar to release the Burmese translation of her novel, an allegory on the military rule in her country, written almost three decades ago. I’m not sure yet how that will be physically possible, as our main character is now in her 70s and it’s risky for her to fly from Europe.

In the meanwhile, I realized as much as I love film, it is really storytelling which is at the heart of my creative ventures. So, we decided to extend the spirit of our company, Old Fool Films, to a wider net of creative projects to include graphics, creative direction in exhibitions and space design, as well as projects focusing on the environment.

I personally have barely left my place, and don’t really see myself filming any time soon.

With the ongoing pandemic and its lingering effects, where do you think is the film industry headed?

I love movie theatres and the collective feeling of experiencing a film on the big screen with other people. It’s really not the same experience as watching a film on a laptop screen. I do hope more people can experience my film on the big screen one day, as it was intended, not just with the images, but with our sound design as well. However, in the meanwhile, I think most content will continue to be distributed online. I imagine the effects of this pandemic will still affect us until the end of next year, so I reckon film festivals will continue to either be screened online or in hybrid form.

It´s obvious that the pandemic has imposed a lot of constraints on the ways we shoot, produce and distribute films. At the same time, I think it’s precisely these constraints that could push us to explore and develop new ways of filmmaking we wouldn’t have looked into under other circumstances. I look forward to seeing the various ways filmmakers will continue to expand the boundaries of the medium despite or because of this global pandemic.

About the Author

Monchito Nocon is presently a public relations and marketing communications practitioner but with substantial exposure to the local film industry. Previously, he was heavily involved in the Society of Filipino Archivists for Film (SOFIA), National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), and the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP).