MANILA, PHILIPPINES — As a traditional narrative, The Boy and the Heron doesn’t quite work. It’s messy, occasionally incoherent, and struggles to fit its massive plot into an already-daunting 124-minute runtime. Thankfully, the narrative isn’t the point of the film; rather, it’s a vessel for master storyteller Hayao Miyazaki’s ruminations on life, death, and legacy as he approaches his twilight years. In this regard, this latest project by Studio Ghibli is perhaps one of its most meaningful, as well as one of Miyazaki’s most personal.

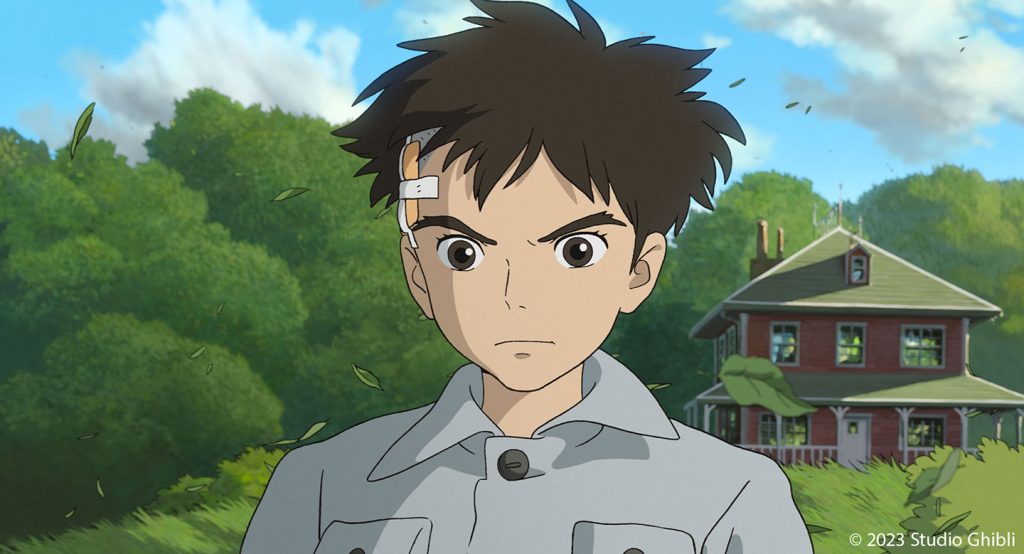

The Boy and the Heron tells the story of Mahito Maki, a 10-year-old boy who moves to the countryside after the death of his mother. A gray heron appears to take a special interest in him, and Mahito is soon dragged into a surreal world where time, space, and matters of more esoteric nature work quite differently from ours.

From the point Mahito embarks on his adventure, the storytelling relies more on emotional beats rather than a clear point-to-point narrative path. The Boy and the Heron requires its viewers to “just go with it” as Mahito does, ignoring the many leaps in logic, narrative inconsistencies, and out-of-nowhere revelations in order to simply feel. While audiences can certainly enjoy the story on the surface level — a fantastical journey filled with memorable characters, whimsical visuals, and engaging stakes — a critical evaluation of the film necessitates viewing it more as an art film rather than a traditional narrative.

Of particular note in this regard is the opening scene, where Mahito runs through a city on fire, desperate to reach his mother. Miyazaki and his team emphasize the emotion of the moment by using motion blur as the key element of the visuals rather than an accent. As Mahito dashes through the flames, his outline turns into swirling streaks of movement, blurring the borders between him, the fire, and panicking masses. What audiences witness in these moments is an impressionistic work of art — think the raw, almost feral strokes of Van Gogh’s Starry Night blended with the pandemonium of Picasso’s Guernica, yet clearly with Miyazaki’s signature style.

It is so distinctively Miyazaki, in fact, that there is a mild sense of voyeurism in watching it, especially when one remembers how some of the director’s earliest memories involve fleeing the bombing of Japanese cities during the war. The scene feels like an attempt to immortalize those memories in the hopes that audiences could feel exactly what he did back then. And that, perhaps, is where the film’s creativity shines brightest: it stirs empathy for Miyazaki himself as he contemplates his life, career, and mortality.

While there are strong parallels between Mahito and the real-life Miyazaki — who, like his protagonist, was the son of a manufacturer of fighter jet parts during World War II — one can see the director mirroring himself in the character of the Great-Uncle, as well. The weary old man ponders the future of the world he’s created, its state growing more tenuous as time passes. The conversations between the Great-Uncle and Mahito at times feel like exchanges between Miyazaki and his childhood self, where there’s an apparent sense of conflict between continuing his stewardship of Studio Ghibli’s imaginary worlds and returning to the mundanity of the real world.

In our real world, The Boy and The Heron comes 10 years after The Wind Rises, which at the time was billed as Miyazaki’s last full-length film as he announced his plans to retire. This context makes The Boy and the Heron’s final scenes rather poignant, as the manner in which both Mahito’s and the Great-Uncle’s choices are made reflect a man struggling to let go of something that has defined his life thus far. The film closes on a shot of an empty room — a rare moment of stillness in a movie bustling with movement in nearly every second of its runtime. There’s a sense of uncertainty about what comes next, but it doesn’t matter; like the 82-year-old Miyazaki, the audience is simply left to reflect.

Audiences looking for something more straightforward may not enjoy this film as much as they might have Miyazaki’s earlier works, but The Boy and the Heron proves that the director hasn’t lost a step as one of the world’s most visionary storytellers. The score is one of Joe Hisashi’s best yet, evoking empathy in moments of sweeping action and in scenes of quiet contemplation. The world of the film stirs the imagination with its visual buoyancy.

But what stands out best to this reviewer is how Miyazaki was able to craft a film rife with end-of-life metaphors, yet still accessible to all ages. It’s a movie that delights its viewers while offering opportunities to reflect on how their own mortality defines the paths they take in life. Heavy stuff, to be sure, but delivered in a package filled with childlike wonder.

The Boy and the Heron’s Japanese title, Kimitachi wa Dō Ikiru ka, means “How do you live?” in English. Through all the pains, the fears, the joys, and the promises that Miyazaki presents with remarkable intimacy in the film, his own answer to the question becomes clear:

“You just do.”

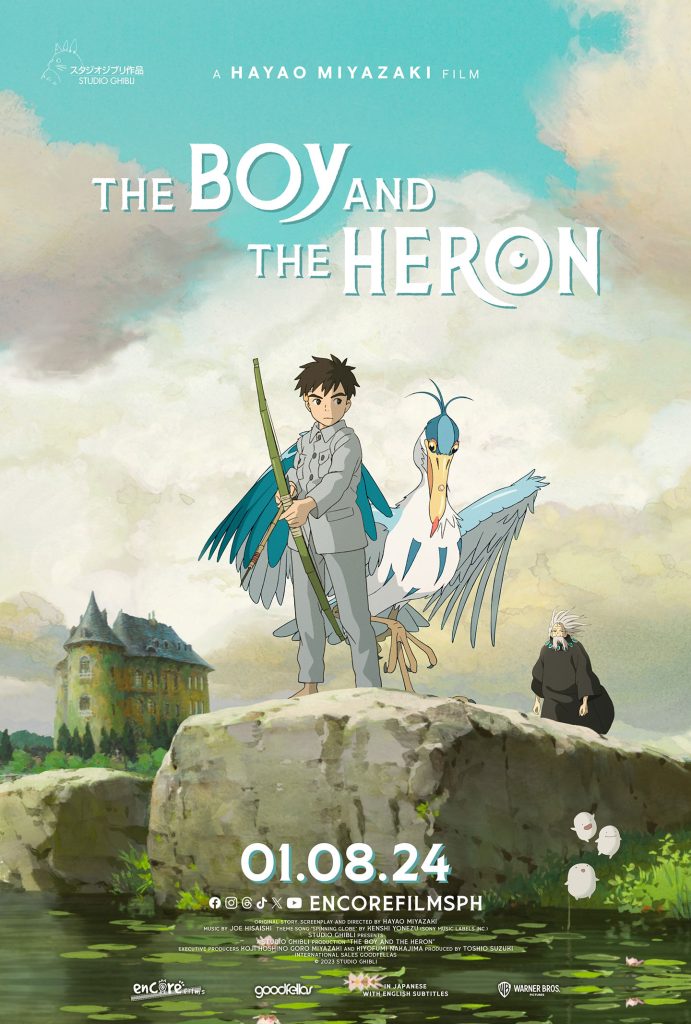

The Boy and the Heron opens in the Philippines on January 08 in cinemas nationwide. The movie will also be available in the English dub in select cinemas.

A special fan screening on January 6 will be open to the public at 7:00pm, SM Megamall Cinema 2. Audiences at this screening will receive exclusive The Boy and the Heron memorabilia.