MANILA, PHILIPPINES – New York-bred dancer Roberto Villanueva did not plan on retreating from the limelight so quietly. Recovering from a bone transplant the previous year did not hinder his performance. Having danced professionally since 1991, Villanueva knew better than to cancel his shows albeit the physical restrictions in his body.

“I strongly believed I had to move forward with the performance. I just had to be careful and listen to my body, and make adjustments on stage as needed. Performing makes me feel whole.”

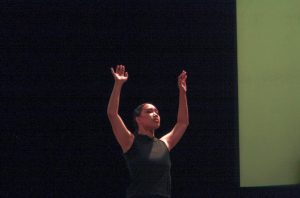

This was apparent from his show “Pieces of Me: An Inside Look at a Filipino-American Dance Artist’s Journey,” performed at the Areté in Ateneo de Manila University on November 14. The show was the last leg of Villanueva’s series of presentations in several schools in Manila, his way of giving back to his birth land, the Philippines.

What was once a one-man show became a collection of solo pieces performed by five young female dancers from the Philippines. Pieces of Me tells the stories of Villanueva’s life at different stages through eleven performances, six of which were danced by Villanueva himself.

He introduces each dance with a brief commentary of when he composed the piece, noting that concert dance is not as easily understandable than one might say pop. In doing so, the audience easily connected with the message of each performance regardless if it is their first time watching or have been a connoisseur for a long time. “I wanted them (the audience) to gain a better understanding of the field of concert dance and the artists behind it.”

Opening with Saborear Esos Momentos (Savoring Moments), Villanueva transitioned the audience into a mellow lull with his slow but fluid movements. This was then followed by a piece he composed in 2014 entitled Incomplete. Performed by CJ Lubangco, Incomplete is a piece that revolves on giving everything without reciprocity—a depth Lubangco showed through mesmerizing backbends and an openness coupled with pained expressions.

Opening with Saborear Esos Momentos (Savoring Moments), Villanueva transitioned the audience into a mellow lull with his slow but fluid movements. This was then followed by a piece he composed in 2014 entitled Incomplete. Performed by CJ Lubangco, Incomplete is a piece that revolves on giving everything without reciprocity—a depth Lubangco showed through mesmerizing backbends and an openness coupled with pained expressions.

Another guest dancer, Misha Bernas, brought about a mood of lightness when she performed the succeeding piece, Destined. Dressed in a white night gown, Bernas filled the stage with wisps of airy body movements; playful but performed with the ease of the character.

The lightness of Bernas’ performance was contrasted by her fellow soloist’s rendition of Unquiet Mind. Camille Imperial showed off her grace amid the chaos central to the piece. Another piece, Caught Up, was danced by Joelle Kamille Bautista. With Bautista’s stage presence and calm but deliberate heaving, the solo that would be the equivalent of denouement in a plot.

Core was particularly noteworthy for its eclectic mix of two cultures; interjecting elements of traditional Philippine folk dance set to the beat of the All Star African Drum Ensemble. Performed by Minette Caryl Maza, Core is Villanueva’s reconciliation of his two cultures. Maza’s impeccable shifts in movement while retaining the audience’s attention is reminiscent of the Maranaoan Gandingan, the principle dancer of singkil; and her calculated twists turned both the candlelight and fan into extensions of her body.

Although the choreography and direction are purely by Villanueva, the performances showcased each dancer’s personality, allowing a firm command of the audience’s interest.

“I believe in honest art,” said Villanueva when asked about morphing his stories into the bodies of the young dancers.

To inject some humor into the show, he danced a crowd-favorite in New York, Child Inside, which he performed bare except for a pair of shorts, knee support, and a stuffed bear. Noting that most audience watch contemporary dance in a heavy air, Villanueva said that Child Inside is his way of balancing things in his show.

The last solo of the show was Arugain. A dance set to the acoustics of Lucio San Pedro’s Ugoy ng Duyan, and against a projection of his childhood photos; the piece was one he dedicated to his mom, and motherland Philippines as well.

Villanueva admitted that it was a show he should have done when he was younger and not when he is nearing his golden year. But his face and physique hardly reveals this, and the fact that he subtly improvised according to his body’s extent. Performance is not lost in him though, as he danced through the show with steady crouches and mesmerizing poses he sustained at his command.

Villanueva admitted that it was a show he should have done when he was younger and not when he is nearing his golden year. But his face and physique hardly reveals this, and the fact that he subtly improvised according to his body’s extent. Performance is not lost in him though, as he danced through the show with steady crouches and mesmerizing poses he sustained at his command.

Watching the show was an exploration of Villanueva’s different faces, and his snippets before the performances provided much sense and dynamics in the otherwise too formal program. He is as much of a host as he is a performer, switching two hats as if cued by the stage lighting.

The show was Villanueva’s last one in Manila but he is hopeful that it is not his final bow. Trusting that his transplant may change its course, he said that he will still perform with certain limitations. After all, a dancer’s instinct to move is as innate as breathing in and out.

“Artistry is not necessarily defined by physical ability,” he added.

However indefinite the future performances of an aging dancer are, Villanueva will surely be a mover even off-stage and continues to be the Artistic Director (and founder) of BalaSole Dance Company.

As he tries to imagine a world where he does not perform, he said: If I don’t dance, it feels like I’m losing a leg.

Great article. Your description of the artists work is impeccable.