A few weeks ago I found myself standing in a sunny courtyard, feeling rather contented with life for three reasons. One: the courtyard was in Barcelona. Two: I was attending OFFF, the annual festival of digital art and design, possibly one of the world’s coolest events. And three: I was about to attend a speech by Stefan Sagmeister, the genius graphic designer whose talks I’d only previously seen online.

Sagmeister seems to have made the search for happiness and fulfilment – indeed, the quest to create a nicer world – part of his brand identity. One of his most popular TED speeches discusses the influence of free time on workplace creativity. It’s true that we are generally encouraged to feel guilty when we’re not working – as if a vacation is merely a self-indulgent waste of time.

As a writer and occasional freelancer, I know this to be false. I’ve done some of my best creative writing while on vacation; and had some of my most career-changing ideas. Your mind doesn’t turn off while you’re on the beach, or mooching around a foreign city. Quite the opposite: it free-associates, mixing new sensations with old and using this rare period of leisure to cook up the results.

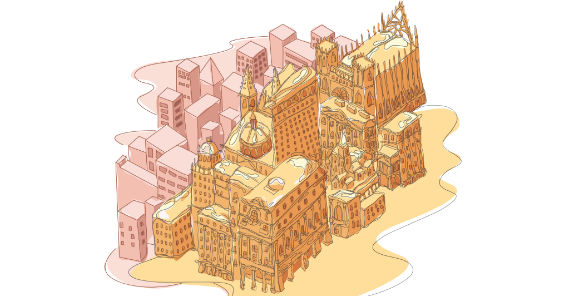

This time Sagmeister addressed a wider question: namely, when did architects decide that functionality was preferable to beauty? And why, as a result, has our planet been blighted by concrete eyesores?

To kick off, the designer mentioned that he once spoke at an OFFF conference in Lisbon. While there he visited a castle, a building “pretty much designed to shoot cannonballs at intruding armies.” Yet it was also beautiful, with symmetrical entrances and intricately decorated doorknobs.

Sagmeister compared this unfavorably to his next conference venue, a Memphis convention center which was essentially a slab of 1970s concrete. “Nothing was designed with beauty in mind.”

What’s worse is that many hotels and apartment blocks – places where people are expected to relax, to live – have been designed with the same brutal functionalism.

Sagmeister put the blame firmly at the door of the Modernist movement, led by the architect Adolf Loos, author of the manifesto Ornament & Crime. He felt that it was criminal to force workmen to waste their time on ornamentation – and that modern buildings should be purely functional.

Loos was a huge influence on the Bauhaus movement, which in turn became “the leading influence on architectural and design thinking throughout the 20th century.” Sagmeister points out that one of the most famous proponents of the Bauhaus movement, Le Corbusier, wanted to tear down Paris and replace it with tower blocks – and an airport.

Coincidentally, and with a certain irony, there’s a current exhibition devoted to Le Corbusier at the Pompidou Centre in Paris. It’s sponsored not by a luxury brand, as many exhibitions are, but by the concrete and cement producer Lafarge. “A house is a machine for living in,” said Le Corbusier. But tell me – do you really want to live inside a machine?

Le Corbusier and his fellow travellers Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius were responsible for a “mass uglification of the world”, according to Sagmeister. Some of their creations were masterpieces; but most of the buildings inspired by them weren’t. Across the planet, developers found that utilitarian buildings could be erected cheaply and quickly. In Europe, the movement was accelerated by the urgent need to rebuild after World War Two. Soviet-style blocks soon began appearing in European, U.S. and Asian cities, a trend that persists even today.

As a Paris-dweller and appreciator of frivolity, I enthusiastically agreed with Sagmeister’s speech. I’ve seen first-hand (as I’m sure you have) that pure functionality doesn’t work for human beings. In the 1990s I lived near the tower blocks of Brixton, London – concrete warrens of misery and drug trafficking.

In Paris, just beyond the ring road (Le Periphérique) that effectively creates a border around the city, lie the troubled suburbs, or banlieus, which contain exactly the same tower blocks, and have bred similar problems – not to mention a small minority of young Muslim men who want to wage jihad either in Syria or at home.

When people come to Paris, they don’t wander out into the suburbs to admire the Modernist-inspired blocks. Instead, they make for the Marais, a low-rise mixture of lovely buildings from the 16th to the 19th centuries, alongside a number of medieval gems, and a blend of quaint boutiques and restaurants. The Marais is pretty – in fact, it is decorative.

One might argue that New York is a city of functional buildings, but nothing could be further than the truth. Its best-loved neighbourhoods – Greenwich Village, SoHo – and its most revered structures – the Empire State, the Chrysler Building – are clearly picturesque. We dream of living and working in these places; nobody dreams of living in a Brixton tower block.

Pure functionality, as Sagmeister argued, doesn’t function. But beauty makes life worth living.

About the author: Mark Tungate is a British journalist based in Paris. He is editorial director of the Epica Awards, the only global creative awards judged by the specialist press. Mark is the author of six books about branding and marketing, including the recent Branded Beauty: How Marketing Changed the Way We Look.

This article was first published in the July-August 2015 issue of adobo magazine.