SINGAPORE — Anybody who uses social media nowadays is likely to have encountered the term “cancel culture” which means boycotting public figures found to be “problematic,” a term usually used by younger generations. It can also take on the form of public shaming, which departs from its original meaning in African-American culture of rejecting oppressive cultural figures or works. Despite the change in usage, cancel culture remains linked to the call for accountability.

Southeast Asia research company Milieu Insight conducted a study to find out Filipinos’ view of cancel movements and what purpose they serve. The study was conducted in July 2022 with 1000 respondents aged 16-40 from the Philippines. The study was also conducted in other Southeast Asia countries, with 1000 respondents each from Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam.

One in five Filipinos have participated in a cancel movement

The study showed that more than four out of five Filipinos have heard the term cancel culture. Moreover, one in five Filipinos said that they have participated in a cancel movement, with the top reasons being that they “did not agree with the actions/opinions of the person or group” (66%), or that “the person or group is/was involved in a controversy” (54%).

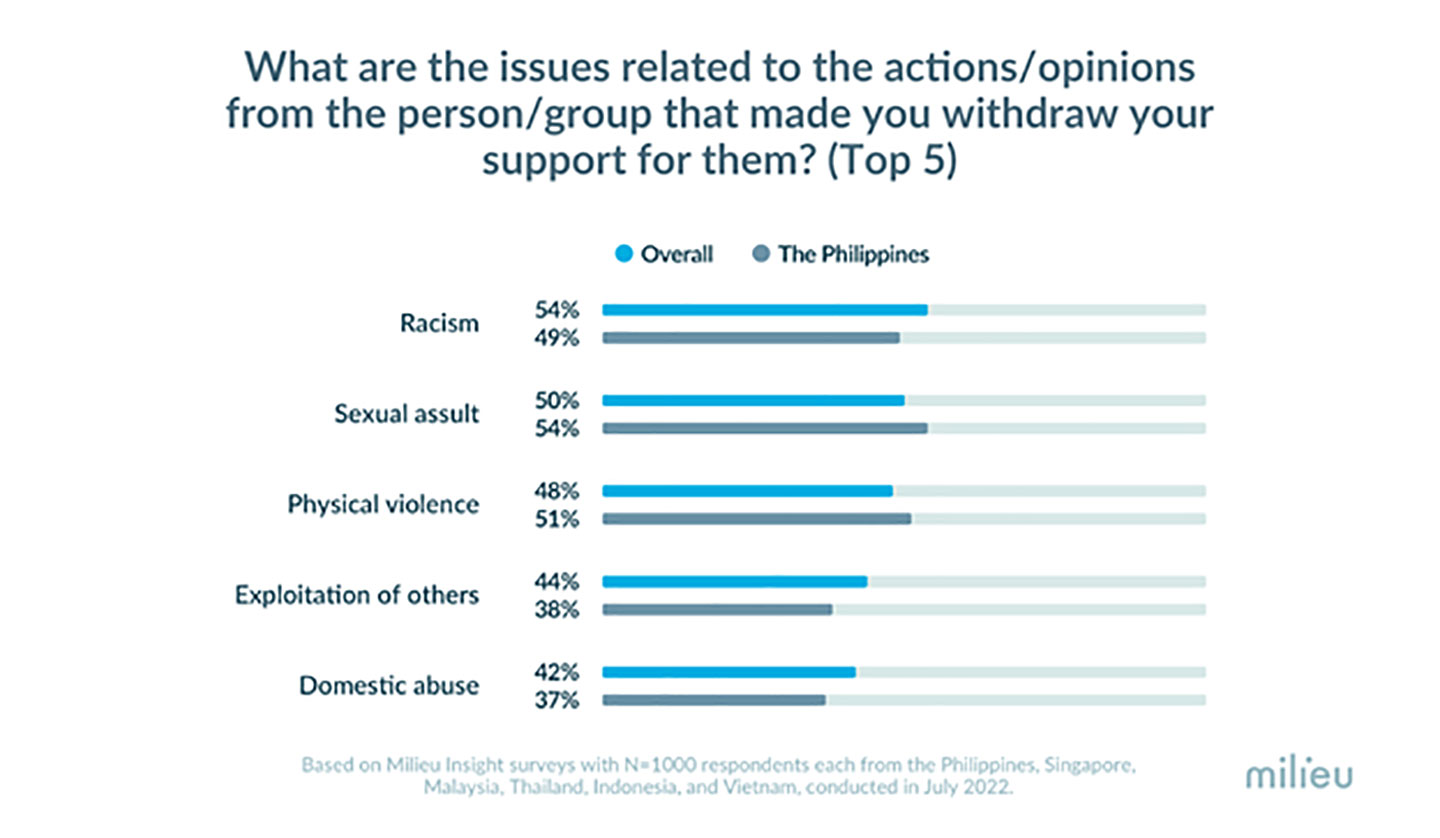

Across Southeast Asia, the nature of the issue that led to respondents’ withdrawal of support tended to be racism (54%), sexual assault (50%), and physical violence (48%). In the Philippines, there’s a skew toward canceling public figures due to cultural issues such as cultural appropriation (50% vs 40% overall), and notably, political stance (48% vs 35% overall).

Does getting canceled spell the end of a public figure’s career?

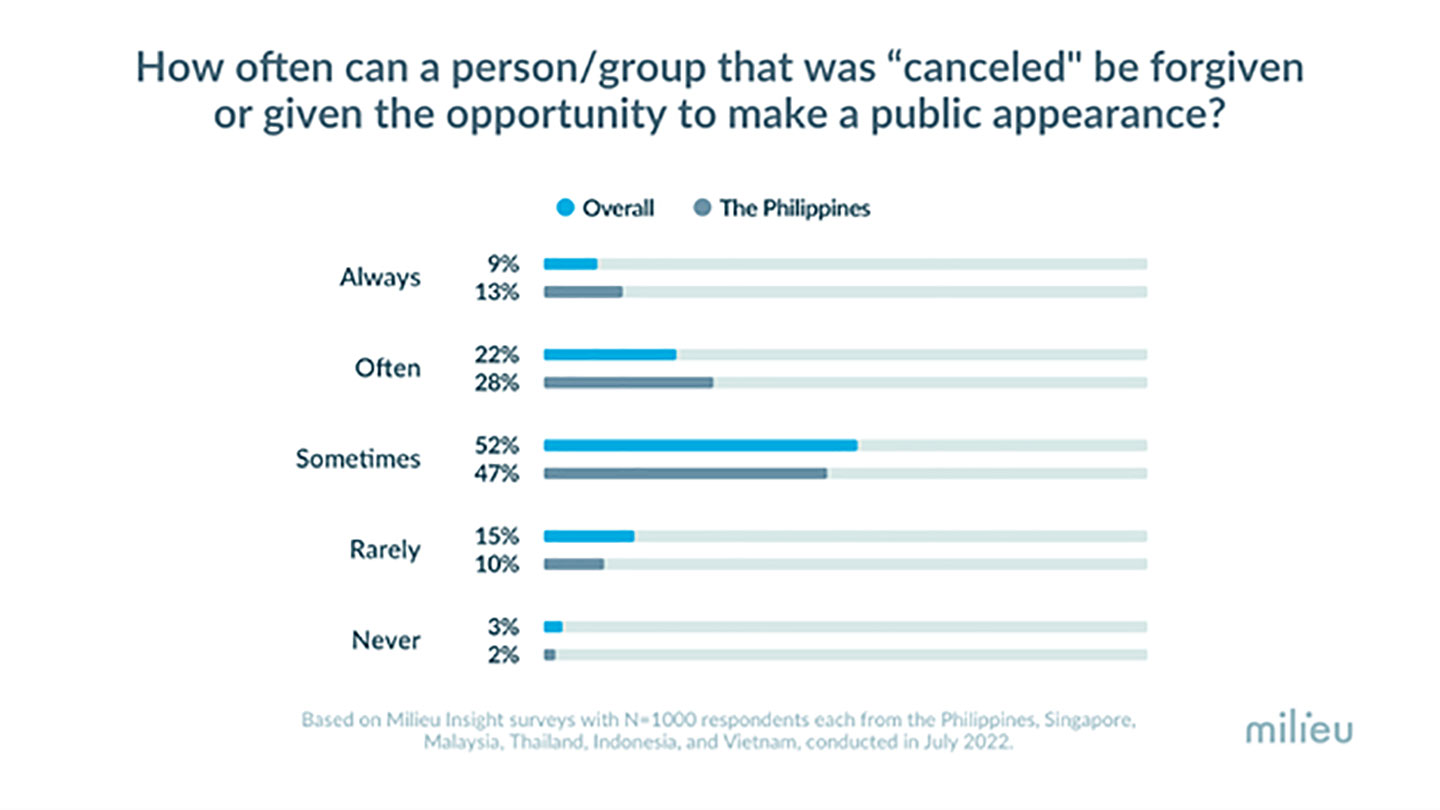

Only 31% of Southeast Asians said a person/group that was “canceled” can always or often be forgiven or allowed to make a public appearance. This sentiment is shared by more Filipinos, with 41% being more agreeable to giving a canceled entity a second chance, the highest rate among the different Southeast Asian countries.

For some, cancel movements serve to direct attention towards the wrongdoings of public figures. Take for example Filipino celebrities such as Iza Calzado and Drew Arellano. Both expressed how the Covid-19 pandemic was the Earth’s way of healing itself and subsequently received public backlash. They subsequently apologized and acknowledged their mistake, and neither of them faced serious damage to their careers. Iza Calzado continued to have endorsements and recently landed a major role in a highly anticipated show.

In other cases, people simply forget or are quick to forgive. It is not rare for a public figure in the Philippines to be let off the hook, especially popular noontime show hosts. Take for example Wally Bayola who had a sex scandal – the host took a leave from his show for six months and admitted that it was difficult to make a comeback when he did return to the show. The public did not dwell on the issue further and a new segment of the show he was part of even achieved 50% ratings, while their rival program had only single-digit ratings.

Majority of Filipinos believe in cancel culture as a tool to demand responsibility

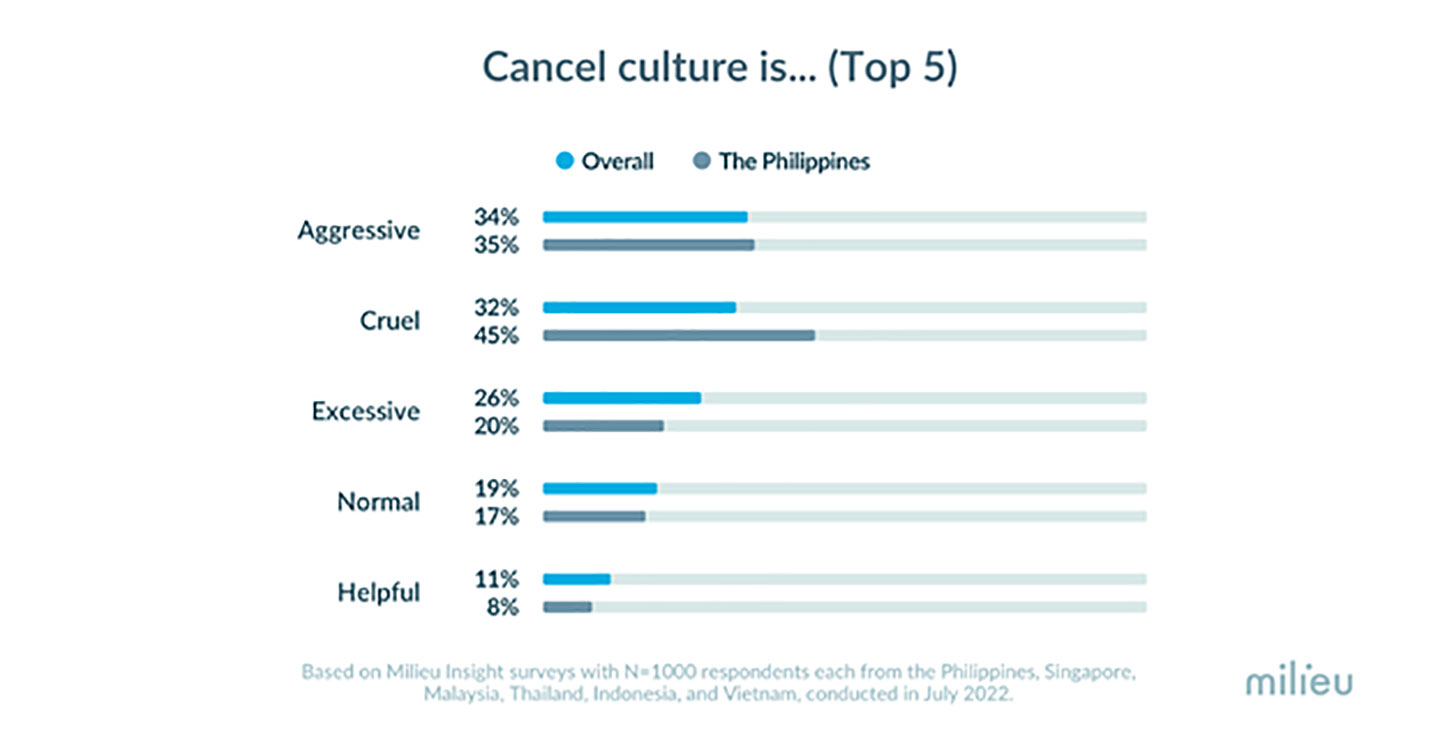

Filipinos surveyed describe cancel culture to be cruel (45%) and aggressive (35%) but those who have been part of a cancel movement tended to view it as normal (30% vs 17% overall), helpful (22% vs 8% overall), and progressive (16% vs 11% overall). This reflects their belief that cancelling is a useful tool to demand responsibility from public figures.

In addition, the majority of Filipinos agreed that cancel movements are a fair punishment (76%) for wrongdoers to be held responsible, and 78% see them as effective in doing so.

From the above scenarios of public figures who were cancelled, cancelling them may not necessarily spell the end of their careers, but rather, bring their wrongdoings to light on the very stage that they stand on: the public arena. Fame is a double-edge sword used against them to demand a public acknowledgement of responsibility for their wrongdoings.

Cancel culture taken too far

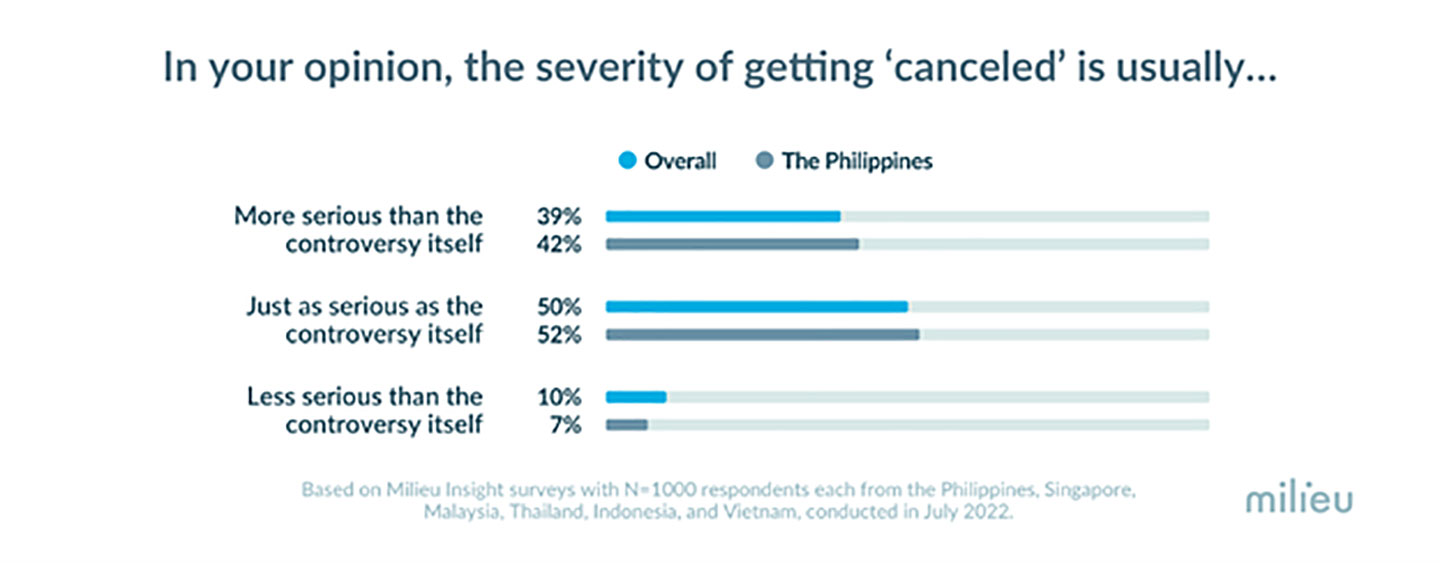

Cancel movements, however, can be taken too far. Most Filipinos (52%) say that the severity of getting canceled is usually just as serious as the controversy at hand. However, a significant number (42%) say that severity is usually more serious than the controversy.

We see this in action when an issue is blown out of proportion or a cancel movement prevents healthy discourse about it. The case of content creator Macoy Dubs shows us that cancel movements have the potential to discourage public figures instead of helping them for the better. Macoy Dubs retired one of his personas after trolls expressed their hate for the character. Instead of providing constructive criticism, the cancel movement centered around voicing their dislike towards the persona. Fans were quick to point out that the persona in question brought joy but Macoy Dubs had already announced his decision to retire it.

51% of Filipinos also say that cancel culture happens too often, significantly higher than those who say it happens just as often as it should (42%). This may be appropriate for a public figure such as Donnalyn Batrolome, who was involved in multiple controversies within a month; however, with cancel culture extending to friends and family, this is worrisome. In the recent Philippine national elections, people canceled not only public figures but also their friends and family due to different political beliefs. It is no surprise then that the majority of Filipinos act cautiously both online (92%) and offline (91%) because they are worried about being canceled themselves.

Given all of this, is it true to say that cancel culture in the Philippines effectively holds people accountable, encouraging change and growth? Or are cancel movements in the Philippines becoming driven by ill intentions? If even everyday Filipinos who have little social power can be canceled, Filipinos could indeed be promoting a more toxic rather than progressive society.