Words by Chiara de Castro; Photos by Jether Dane Guadalupe

“I am not a minimalist.”

Patrick Cabral tells me this, as I make a sweeping survey around his apartment: the place is neat, but far from sparse. At a glance, it’s evident that the young artist, as well his wife, Camy Francisco–Cabral—also an accomplished artist—likes things, whether it’s coveting them, collecting them, or making them. By the entrance, a tower of stackable containers provide shelter to an impressive number of assorted footwear, most of which are sneakers (I assume the collection is a conjugal one and neglect to ask whose is what). On one side of the apartment, an entire wall is lined with panels dedicated to books and collectible gures and various knick knacks that arouse curiosity as much as nostalgia; several are remnants from the past, varying from treasured childhood toys (e.g. a pizza-shooting Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles tank, owned by Francisco-Cabral) to recognizable Funko characters on display without their boxes (proudly owned by Cabral, while their respective boxes are stowed by his wife).

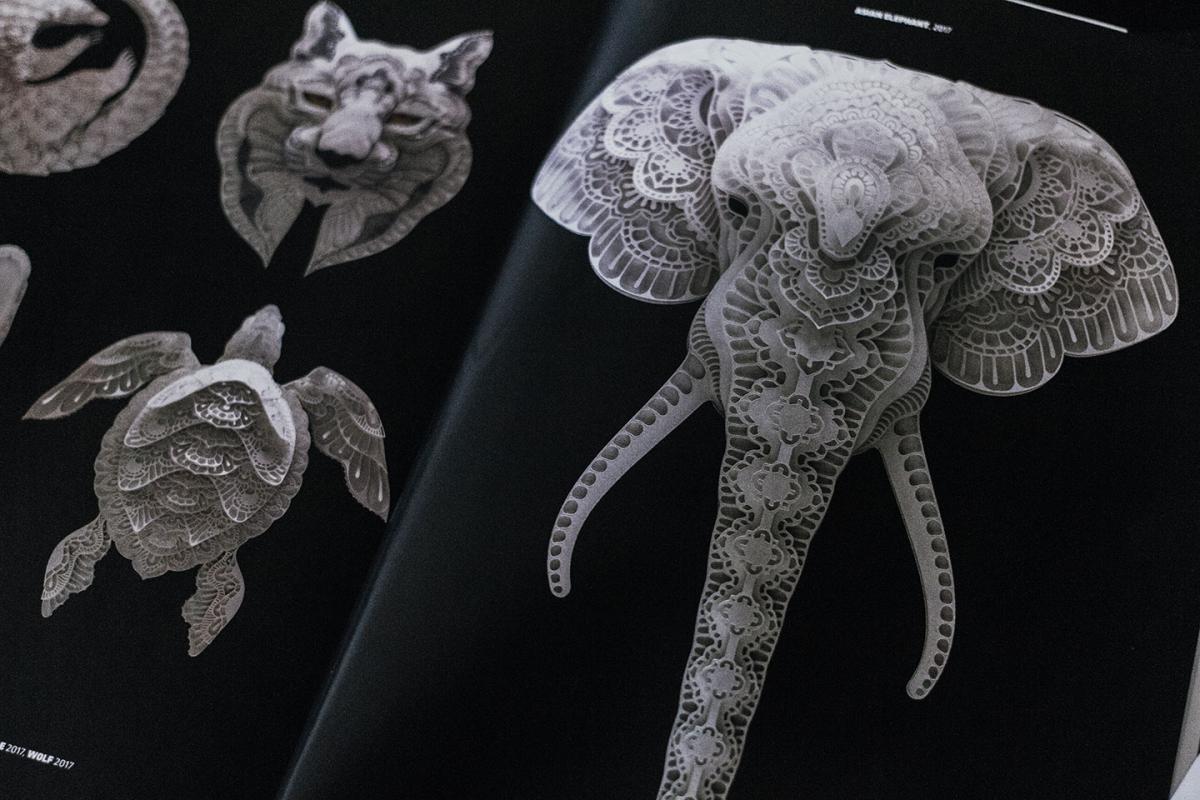

The wall across, on the other hand, bare on display frames upon frames containing some of Cabral’s best work to date. Enclosed in its own glass box, a tiger sculpture stares back at me from the wall. I stare back, transfixed by its lifelike stare as I am with the intricate layers of paper it was constructed with to achieve its three-dimensional relief effect. How can something seemingly so simple as paper be so elaborate and ornate at the same time? Cabral chuckles at this, sharing that it’s a thought he’s heard of numerous times. “Some people have dismissed my artworks, saying these are just mere cut-outs from paper, but when they finally see it up close, they wonder how I actually made them.”

The enigmatic tiger is just one of the 11 endangered animal paper relief sculptures in Cabral’s series for World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), wherein 50% of the proceeds from each sold artwork would go towards the organization’s conservation e orts across the globe. Several reports have claimed that this is the project that had catapulted Cabral into the international art market, boosting the price of his work into the six gures. Something that Cabral is far from apologetic about. “I’ve worked really, really hard my entire life to get to this point,” he shares. “And every single piece of artwork takes a lot of work to construct; a lot of time, a lot of thought and attention goes into each of my works.” He pauses for a moment, shaking his head as he gnaws on his thoughts. “Why shouldn’t I put a price on my hard work? I’m practical and I’m realistic; yes, I love art, but this is work and I work to earn and survive and have a life—just like every other person who’s trying to make a living and make something of themselves. Why should I be ashamed or shy about that? Hard work is hard work.”

Among his recent notable projects is the commissioned paper-cut sculptures by Starbucks, which are on display in the Starbucks Reserve® store in SM North Towers in Quezon City, depicting animals that represent each of Starbucks’ coffee-growing region: The Sumatran Tiger for Asia Paci c, the Kenyan Elephant for Africa, and the Guatemalan Quetzal Bird for Latin America. Cabral was also chosen as one of the ambassadors for Starbucks’ “New Strong” campaign which celebrated modern- day strengths while empowering individuals to break away from the mold and nd their own de nition of ‘strong’. As an ambassador, he created a stunning paper-cut typography piece for the campaign.

I ask him if he always intended to be an artist, perhaps a reason for his segurista (calculated, no-room-for-error) approach to almost everything he sets his mind to in his life. Cabral tells me no, that this was far from the realities of his youth, as a child growing up in the humble parts of Olongapo City and Camarines Sur. “I got into art because I constantly had to make something with my hands; I guess it was a need to constantly be productive, to create something useful,” he recalls. “We were poor when I was growing up, and at a young age, I already knew that if I wanted something I had to figure out how to make it. It would never just be handed to me.” He shares that he developed his competitive tendency in his early years, driven by the inherent need to rise above his peers in school and in his community. “You know how in schools, there would be these contests and competitions? These were opportunities to win prizes, to get elevated, to nally get out of there.” Cabral chuckles at the memory. “I had some classmates who could draw really well and would win these contests. But they didn’t have the drive to become really good, to be able to live a much better life. Some of them are still there; same place, same life.”

His wife chimes in, pointing out his meticulous, methodical approach to producing his artwork. “His technique is very calculated, very logical, practically mathematical,” Francisco-Cabral describes. “It’s nothing like your quintessential starving artist’s style, because he lived his entire life believing that you only have one shot at making it in life and everything is earned, that nothing is ever just given to you. And the only way for him to have a shot was to be the best—in everything he did. And if there was an opportunity for him to earn more, to live in a better place—whether it meant learning code to develop websites and graphic design because the digital market was ripe—he would teach himself and master it.” She proceeds to explain the idea of overcompensation, something that she believes truly describes Cabral’s approach to life and work. “Imagine having spent your entire life since childhood believing that the world is a battleground and success is the only way out. Of course there’s no room for error for him, of course it has to be perfect.”

While the couple hail from extremely opposite backgrounds; hers being the more privileged and comfortable life, they clearly have learned from each other both as artists and as individual adults just trying to make it while doing what they love doing the most. “I was a very stubborn and diffcult child and I know my parents really struggled with me,” Cabral intimates, and I detect a tinge of sadness in his voice. “They wanted me to have a ‘real profession’ and so their struggle of raising me would be worth it. But I couldn’t just do work every day that I’m not interested in—I can’t live like that. So I needed to prove—to them, to myself— that what I do can actually give me a good life.”

In addition to crediting Francisco-Cabral for her impact on his creativity, as well as for her steadfast support, Cabral reflects upon the other person who stood by him without fail throughout his entire life. “My younger brother has always been a great influence on my work since we were kids,” Cabral says thoughtfully, recalling childhood memories laced with healthy competition and punctuated by fondness. “He is probably the most hard-working and resilient person I know, and he continues to inspire me to keep working harder, to keep working better. He helps me with my artworks, because he’s so good with logistics and dealing with people. I don’t know if this would all be the same without him.”

While the couple are unable to disclose the details of their next project, they share that they’re both restless and ready to get back to work. “Patrick is definitely more organized and methodical with his process, while I work in bursts,” Francisco-Cabral shares, as we peruse some of her own unpublished typographical illustrations. “But I guess when you get used to a cycle of months of intense work, followed by months of rest, you can’t help but look for that intensity of grit and the flow of work again, you know?”

Needless to say, we are brimming with anticipation for their next masterpiece.