by Rome Jorge and Rea Gierran

It is a touching true-to-life story of a cavalier knight-turned-ascetic saint, set during during the tumultuous epoch when the Spanish Inquisition terrorized both the faithful and the free-thinking alike; when the Counter-Reformation saw Catholic stalwarts battling Protestant reformers with devotional theology, baroque artistry, and the murderous 30 Years War; and when the Age of Discovery witnessed European empires colonize, enslave, and convert entire civilizations across the globe.

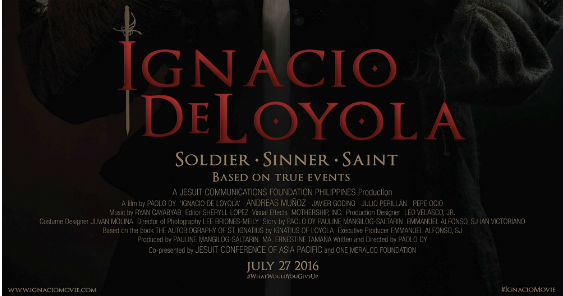

It is a gorgeous and expensive film shot on location amid the medieval ramparts and breathtaking landscape of the Basque Country and the Navarra regions of Spain with over 400 lavish and accurate period costumes, armor, and weapons that stars all-Spanish cast known for their roles in films such as Woody Allen-directed Vicky Cristina Barcelona, Oscar Award-winner El Secreto de Sus Ojos, Madonna-starrer Desperately Seeking Susan, and Goya Award-winner Yo, Tambien, and that was directed behind the scenes by Paolo Dy and the rest of his all-Filipino production team that includes Ryan Cayabyab for music, Lee Meily for cinematography and second unit directors Cathy Azanza, Eduardo Huete, Aaron Palabyab, and Bombi Plata, to name a few.

Ignacio de Loyola, the movie, premiered at the Solaire Resort and Casino, Parañaque City, Philippines on Saturday, July 23 with live scoring by the ABS-CBN Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of Maestro Gerard Salonga. It screened privately Power Plant Mall Cinema, Makati City, Philippines on Monday, on July 25 for for friends of adobo magazine. Then it opened to the public on July 27 nationwide at select theaters at SM, Robinsons, and Ayala malls. International screenings are to follow.

Ignacio de Loyola stars Spanish actors Javier Godino, Isabel Garcia Lorca, Pepe Ocio, Julio Perillan, and Andreas Muñoz in the titular role of Ignacio.

Ignacio De Loyola is better known as Saint Ignatius, founder of the religious order of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) that run the exclusive Catholic school Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines. The movie was produced by the Jesuit Communications Foundation, the media arm of the Philippine Jesuit Province and co-presented by the Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacific and One Meralco Foundation.

More mortal

Every Atenean knows the story of St. Ignatius: A knight who gets injured by a cannonball on the battlefield and turns to religion instead. The movie adds context and complexity to his story.

Born Íñigo López to Basque royalty in Loyola on October 23, 1491, Ignatius was already a leader at 29 years of age when he was grievously wounded on May 20, 1521 while defending Pamplona’s fortress from the French-Navarrese army. After enduring several excruciating operations without the benefit of anesthetics, he walked with a limp for the rest of his life. During convalescence, he read numerous books on the life of Jesus Christ and the saints, igniting a desire in him to lead a life of denial, devotion, and pilgrimage, wishing to tread the footsteps of Saint Francis of Assisi and the conversion of non-Christians in the Holy Land.

His zeal in preaching the word on the street as well as the ecstatic reactions of his female followers aroused the suspicions of Inquisitors who suspected him of being an alumbrados (illuminati). He was however released. Later, he attracted a few loyal companions, notably Saint Francis Xavier and Saint Francis Borgia, who swore absolute loyalty to the Pope as the Society of Jesus. In a curious turn, Ignatius, who was enamored with self-denial and suspected by Inquisitors, would lead the Jesuits that spearheaded the Pope’s counter reformation and forge it into one of the Church’s most powerful orders before passing on at aged 64 in Rome.

Stranger in a strange land

Dy shares with adobo magazine that Ignatius’ character resonated with the Filipino director on a personal level. “Ignatius had a tendency towards obsession and perfectionism—something that almost destroyed him, but in the end, he found a way to master it and use that tendency for good. I think all artists worth their salt will be able to relate to that. On many levels and on many fronts, this film has been a learning experience for the whole team, and I feel like it’s made me a better filmmaker, visualist, and storyteller,” he confides.

Muñoz, who plays Ignacio, also saw himself in the saint. “What I see similar is that he’s a man who listens, a perfectionist, ambitious, a bit vain sometimes, very stubborn, I can be like that. Lastly, the element of being human. Ignacio and I has a lot of humanity. When it comes to difference, I would say that he’s much more disciplined that I am. I learned how to be patient, to persevere. I didn’t have a lot of patience before acting out the character, but after filming it, I became a lot more patient,” he shares.

Dy reveals that working on location in Spain was an eye-opener. “We had to sort out and mediate a lot of differences in cultural norms and working styles. The Spanish lunch is not until 2 or 3pm and we Filipinos tend to get cranky if we don’t get lunch by 12:30pm. Then too, the working hours are regulated by government and union rules—a limit of 10 hours of shooting per day, plus one hour for lunch. And lunch is a very civilized event: you must be seated, the meal must be hot, it should have three courses and there’s a minimum of one hour allocated for it. In addition, that one-hour clock doesn’t start until the last person has been seated and has started eating. The limited work hours forced us to be more focused, efficient, and more prepared. Certainly it forced me to be absolutely clear about what I wanted from each scene, and attack that core intention without needing to get alternate takes. I didn’t shoot any ‘options’ on this film, and I think the film is all the stronger for it.”

Muñoz also had to fly to the Philippines to work on a few pivotal scenes. He recalls, “It was cool. It was great. Ninety five percent was done in Spain and then they brought me here in Manila to film the river scene, and as well as the cliff. It was quite an experience for me because I’ve never been in Asia. It was nice to see how Filipinos work here. They’ve been really professional, and wonderful.”

Shooting a movie at two different locations posed challenges upon Muñoz, whose intensity onscreen was remarkable. “Believe it or not we started to film that scene in Spain, and then three months after we finished it in the Philippines. I had to keep the continuity of that scene. That was the challenge for me, to continue what I was working on before, in July and maintain that energy at the end of October. I prepared mentally. I concentrated hard. The director helped me a lot, Bombi Plata and the rest of the team. I just had tor remember what I was feeling that exact day and extrapolate that on the cliff. I gave not only 100, but my 1000 percent on that performance. I gave all of myself to it. After filming that scene there wasn’t any Ignacio or Andreas left with myself. I was empty. That’s what I said to my family. I need to recover because I’m empty.”

The Filipino director has nothing but praise for the Spanish cast. “They were highly trained in both theater and film, and they came to the set completely prepared. The theater training also meant they were meticulous about everything from their manner of speech to the costumes and props they were assigned; they would ask for adjustments in these if they felt like it didn’t jive with what their character would actually wear or use. I appreciated the care with which they built up their characters, and I think it shows in the finished film,” he notes.

Muñoz, in a separate exclusive interview with adobo magazine, unknowingly reciprocates the admiration. Speaking about the director, he shares, “He’s such an amazing person, such an intelligent director. I love working with him. I love him as a person and as a director. I think that he’s a genius. He’s got everything on him. He’s got every single detail controlled and he knows exactly what he wants so for me, he’s a genius. I hope the world sees that.”

Philippine perspective

Ignatius was age 29 when on March 16, 1521, Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese in the service of King Charles I of Spain, the same monarch Ignatius would risk life and limb for, arrived in Homonhon, Philippines and, together with many of his rapacious crew, was slain by Lapu-Lapu of the kingdom of Mactan, one of the first Asian heroes to successfully repel a European invader. However, for the next 300 years, the Philippines languished as a colony of Spain. Today, the Philippines is 83% Roman Catholic and is only one of two Christian majority nations in Asia. In this context, it seems only apt that the Philippines produces a film on the life of the Spanish saint, as while Spain has progressed into secular modern democracy that enshrines the rights of women, reproductive health, and marriage equality, the Philippines continues to be the only nation without divorce, with the highest rate of HIV/AIDS infections in the world, with the highest rate of teenage pregnancy in the Asia-Pacific, where plunder and corruption have been entrenched generations of popularly elected political dynasties, and where extrajudicial killings have recently received an electoral mandate as tacitly part of the incumbent president’s “war on drugs” platform.

Ideally, by seeing how Saint Ignatius lived during the time of the Spanish Inquisition and the Counter-Reformation, Filipinos will seek to have a more critical understanding of how their own identity came about as Filipinos. Naturally, some of those who have yet to watch the movie question wether a film funded by Jesuits can fearlessly and honestly portray both the man and his milieu as well as wether a film about the life and times of a saint can appeal beyond the devoutly religious. To its credit, the “Ignacio De Loyola” is a pleasant surprise.

Brilliance and stardom

Ignacio de Loyola deserves lavish praise for its gorgeous cinematography and costume designs and the cast’s intense and sublime performances onscreen. “Gorgeous” pertains to the work of all the directors: Dy, Azanza, Huete, Palabyab, and Plata. This excellent ensemble work is apparent as there was hardly any scene that was not painterly and well composed. “Gorgeous” also pertains to James Reyes’ intricate and historically appropriate works. “Intense” pertains Muñoz’s fiery and riveting portrayal of the saint. And “sublime” pertains to Lorca’s deft, poignant, and at times humorous portrayal of Doña Ines Pascual.

Little can be faulted in the film. The sound editing could use more depth, dimensionality, and subtlety. The sound of objects all felt as if they were right next to one’s ear. The sword fight sequences were sparsely populated, as if Ignacio fought in a duel instead of a battlefield. And the computer-generated imagery was apparent, at times failing to seamlessly blend with actual location shots.

Saying and not showing

As for the narrative itself, Dy and the other director/writers should be commended for choosing Ignatius’ trial by Inquisitors as the climax of the narrative, which portrays zealous members of his own Catholic Church as his antagonists, accusing him of being an Illuminati.

The Inquisitors in the film clearly state that they have burned to death alive at the stake many others they have found guilty of heresy—simply thinking and believing differently from official Church dogma—and threaten to do the same to Ignatius. However, this is said and not shown. The mortal peril that Ignatius faces and the constant terror that everyone feared during his milieu is not visually established.

Alarmingly, one of Ignatius’s Inquisitors is portrayed sympathetically—shown aiding the saint to obtain theological education in France, as if the Inquisitors’ acquittal of Ignatius makes the death sentences the film states that they handed out to the countless others they condemned and burned alive at the stake for simply believing and thinking differently was any less monstrous and unforgivable.

The film must be commended for its sensuous, humorous, and at times irreverent portrayal of the man who would be saint. His self-flagellation as a cave-dwelling hermit can be seen by skeptics as indulgent masochism. His struggle with the devil/former self in the surreal Mount of Temptation of his own mind can be seen by skeptics as a descent into madness. And despite scenes that indulge both the protagonist’s religious ecstasy and his Catholic guilt, Ignacio de Loyola is a film that can be enjoyed by skeptics and the pious alike. Regardless of religion, it is a film worth watching.