Art museums and exhibition sponsors are exploiting digital and social media in subtle new ways.

They call me the anti-Christ of the art world,” Bas Korsten, executive creative director of J. Walter Thompson Amsterdam, told me. Surprisingly, he did not look depressed by this description. Perhaps that’s because he was sitting on the JWT boat in Cannes and had a line of Gold Lions on the shelf behind him.

What had Bas done to merit such a dramatic response? If you followed the news from Cannes, you already know. To cut a long story short, Bas and his team created a “new” Rembrandt painting using artificial intelligence and a 3D printer. Once the machine had been fed with everything it needed to know about the artist’s painting style—not to mention 17th century clothing — it got to work, eventually producing an eerily plausible Rembrandt portrait.

“What’s the point?” you may ask. In fact, the client was the Dutch bank ING, which wanted to draw attention to the fact that it is a longstanding supporter of the art world. These days, however, sticking your name on an exhibition poster is not enough. Sponsors, and indeed museums, need to create buzz.

The Next Rembrandt, as the artificial intelligence project was called, certainly achieved that. And although it provoked controversy, it was actually welcomed by some scholars, as it unearthed a few interesting new facts about Rembrandt’s work and life. For example, by analyzing the artist’s actual canvases, the project team noticed similarities pointing to the fact that he’d bought them all from the same supplier.

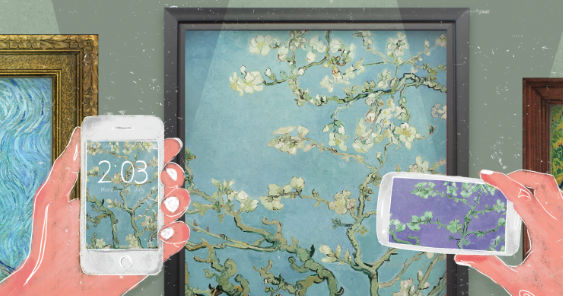

I first noticed a thawing in the relationship between the digital and art worlds in May 2015, when the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York re-opened in a new building. Apart from the stylishness of the museum itself—which was designed by Renzo Piano —I noticed all the millennial visitors snapping artworks with their phones.

In Paris, where I live, you barely have time to think about removing your phone from your pocket at an art museum before a security guard hustles up and tells you to put it away. When I asked a guide at the Whitney if I could take pictures, she said: “Sure, just don’t use the flash.”

In fact, she told me the museum actively encouraged visitors to post pictures on Instagram. I later read that #NewWhitney had generated more than 6,000 Instagram images in the first week of opening, and that it was positioning itself as one of the world’s most social museums.

A new trend began to come into frame, if you’ll excuse the pun, when I learned of an innovation at Rubens’ House in Antwerp. The museum was using iBeacon transmitters—wall-mounted devices resembling grey plastic pebbles —to send additional information about the artworks and objects on display to visitors’ smartphones, via an app. This provided a deeper and richer visit, dispensing with clunky audio guides and hit-and-miss QR codes, which now feel as if they come from another century.

Crossing the Atlantic again, Leo Burnett has run a couple of great campaigns for The Art Institute of Chicago. In 2014, its Unthink Magritte campaign (for the exhibition “Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938”) turned the entire city into a canvas. Starting with fairly conventional posters, the campaign got increasingly…well, surreal. Black bowler hats, umbrellas and fluffy white clouds began appearing in store windows. A giant sculpture of a pair of feet appeared on a local beach. And on opening night, visitors could trade surreal objects—a glass eye, a plastic scorpion—for free admission to the show. Once inside, an app enabled them to share, comment and find out more about the art.

In February, Leo Burnett and the Art Institute of Chicago struck again for a show devoted to Van Gogh. This time, the museum partnered with Airbnb to create a three dimensional, human-sized reproduction of the artist’s bedroom — as featured in his painting “Bedroom in Arles” — and invited people to rent it for the night. Imagine your Instagram followers slicing their ears with envy as you post pictures of the ultimate arty pad.

To a certain extent, though, social media is old news. As we’ve discussed in these pages before, Virtual Reality is the latest big thing. So how about using it to explore Salvador Dali’s brain?

That’s (more or less) what the agency Goodby Silverstein did for an exhibition at the Dali Museum in Florida recently. It created a VR experience for the exhibition “Disney and Dali: Architects of the Imagination” (which ended in June). You may not have known — I certainly didn’t — that Disney and Dali once worked together on a short animated film called Destino. Yes, really. You can find it on YouTube.

Even weirder than the film itself, Goodby’s VR tour allowed users to explore a 1935 Dali dreamscape (“Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet’s ‘Angelus’”) using an Oculus Rift. They could float around the strange sculptures in the painting, as well as bumping into other surreal figments of the artist’s imagination. Frankly, I’m surprised they didn’t claw the Oculus from their faces and run a mile in the other direction.

If you’re an art lover, you may think it’s enough to simply stand and gaze at a beautiful painting. But many of today’s museum visitors think of themselves as artists in their own right, so they want to get closer to the experience of creation. Museums are happy to indulge them, especially as it means selling more tickets.

Mark Tungate is a British journalist based in Paris. He is editorial director of the Epica Awards, the only global creative awards judged by the specialist press. Mark is the author of six books about branding and marketing, including the recent Branded Beauty: How Marketing Changed the Way We Look. This article was first published in the July-August 2016 issue of adobo magazine.